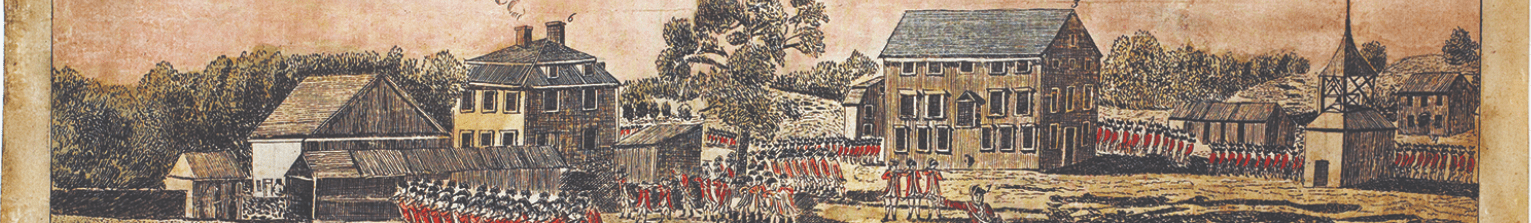

On April 19th, 1775, a half hour before sunrise, the British regular army killed eight American men in Lexington Massachusetts, an event marked by many as the start of the American Revolution. What happened in the moments before these men died became immediately enshrouded in finger-pointing and, later, academic debate that has lasted for 250 years. Did the British open fire “without provocation?” Or did the Americans first “give them a fire?”

The answer today, like always, depends on who is asked.

Some cling to the narrative that has prevailed in America since the day of the fight: When the town militia failed to leave the field quickly enough, a mounted British officer rode onto their village green ahead of the King’s troops, fired his pistol, then ordered the men behind him to open fire. The instigators, the Americans all agreed, were the British.[1]

Over the last century, on the heels of additional British accounts becoming public, a new narrative emerged: The British commander repeatedly told his men to not fire, but when an American off the field fired at them, the soldiers rushed forward without orders and fired back at everyone they saw. In this retelling, the British commanders are cleared of fault. An anonymous hothead American started the revolution, not Major Pitcairn and his lieutenants.[2]

Which account is correct? Arguably, neither. For starters, both are incomplete, based on selected eyewitness accounts but not all eyewitness accounts. Accepting either version—or any other theory—has always been assumed to require judgment on which witness statements are credible, judgments inherently susceptible to the biases of the historian. The patriot tales flatly rejected Pitcairn’s official report. More recent “apologist” retellings shamelessly dismiss sworn American statements as “dubious” [Beck] or “the long-winded recollections of old men” [Tourtellot] or “best left to appendices” [Murdock].

This perceived need to pass judgment on witness quality carried an implicit assumption that the British and American statements cannot be reconciled. Historians seem to think that, since these men fought each other on the field, their statements must also conflict. Someone lied about what happened, right?

Not necessarily.

What They Said Happened, Collectively

What if instead of passing judgment on witnesses, favoring some while marginalizing others, we instead ask the question: What does the story of Lexington Common have to be if everyone did their best to tell the truth, just not all of it?

This is a better assumption than one might think. Eyewitnesses had either little incentive to lie outright (e.g. in a personal letter) or a distinct disincentive (perjury). They did, however, have plenty of reasons to carefully select what they reported, stating those facts that best justified their actions while omitting inconvenient details that might result in bad optics.

Therein lies a great untapped opportunity. While no one told the whole truth, if every witness recorded some truth as accurately as they could, and their silence about all other events amounts to de facto agreement (as it would in a court of law), we might be able to recombine all their partial truths into an approximate whole truth.

Aiding the effort: Surviving eyewitness accounts are structured in sequenced statements separated by words like “then” and “a little after” to signal that one event occurred after another, plus occasional triggers like “meanwhile” to indicate a break in the chronology. We can therefore break down each eyewitness statement into granular events, keeping them in order, then line them up where two witnesses describe the same event, forming a long sequential chain that agrees with every known account.

To illustrate, consider the following partial statements of three British officers known to be present:

- Ensign Henry DeBerniere, an expedition guide, wrote in his report of the day: “Major Pitcairn ordered our light infantry to advance and disarm them, which they were doing, when one of the rebels fired a shot. Our soldiers returned the fire.”

- 4th Light Infantry Lt. John Barker wrote in his diary: “we still continued advancing, keeping prepared against an attack tho’ without intending to attack them, but on our coming near they fired one or two shots, upon which our men without any orders rushed in upon them, fired, and put them to flight”.

- Marine Captain William Soutar wrote in a personal letter: “The van company of the light troops . . . after a report and whistling of two balls fired on it, the light company, on hearing a shout from the leading company, immediately formed and a fire was given.”

In isolation, these statements appear to conflict (and we haven’t even gotten to the Americans yet). Did Major Pitcairn give the orders to advance or not? Did a British officer command the troops to fire or not?

Many researchers pick the statements they like and ignore the others, akin to a paleontologist reconstructing a dinosaur skeleton but leaving half the bones in storage. If we instead assume all statements are true in some context, we have to conclude apparent “conflicts” are, in fact, descriptions of different moments in time. For statements with multiple interpretations, we consciously choose the interpretation that fits best with all the others.

Breaking down the three officer’s statements into individual events, then lining them up, we arrive at the following “best fit”:

| DeBerniere | Barker | Soutar | “Best Fit” |

| Major Pitcairn ordered our light infantry to advance and disarm them, | Pitcairn ordered the light infantry to advance and disarm the militia. | ||

| which they were doing, | we still continued advancing, keeping prepared against an attack tho’ without intending to attack them, | The light infantry crossed the common. [The 10th led, followed by the 4th] | |

| when one of the rebels fired a shot. | but on our coming near they fired one or two shots, upon which | The van company of the light troops [. . .] after a report and whistling of two balls fired on it, | The front company heard a shot they thought came from the militia |

| on which the light company, hearing a shout from the leading company | The “leading company” [the officers on horseback at the front] shouted, in response to which. . . | ||

| Our soldiers returned the fire. | immediately formed and a fire was given. | The [10th] light infantry formed and fired. | |

| our men without any orders rushed in upon them, fired, and put them to flight | After which, soldiers rushed in without orders [possibly from Lt. Barker’s 4th, which had no captain] and continued the firing. |

We can further expand this “best fit” narrative using statements from other British eyewitnesses, which add details such as the names of the officers in Soutar’s “leading company” (which did not include Pitcairn), Major Pitcairn’s shouted orders during the advance, and the source of the rebel shot (off the field). Then adding the American statements serves to clarify details such as what the leading company shouted that precipitated the British fire (“Fire! God damn you, fire!”), what happened when the “men without any orders rushed in”, etc.

The Americans also naturally touch on events not covered by any British source. The British statements alone imply the Americans fired first, but not so fast! Their accounts nimbly skip over much of what happened.

Can a “best fit” extend across the entire fight? Perhaps sixty American and ten British witnesses said something about what happened in some forty different written statements. Is that enough bones to reconstruct a complete skeleton of the day, two and a half centuries after the fact? Do they all fit together?

It appears so. There is some art involved in producing this kind of collective statement, but no magic. Anyone can perform the exercise using widely available source material (see the Reference Index below if you want to try). Some narratives do not fit perfectly (it would be suspicious if they all did). There are discrepancies in estimated times and distances and other details, and the Americans call the ranking British officers by the wrong names (see here for that story). But overall their statements line up nicely. Our “best-fit” fills in the holes left in various individual statements and helps identify (and correct) what are arguably good faith errors.

In all, our reconciliation describes over two dozen distinct actions and reactions between the arrival of the British and the retreat of the Americans. In virtually every instance, at least one eyewitness reported the event with some detail, one or more others said something close to it, and no eyewitness said the event didn’t happen.

It might be the first version of the fight that agrees with every statement.

Read Next

The play-by-play: The Best-Fit Version of the First Shots

The punchline: So, Who Shot First?

References

This section lists eyewitness statements used to construct the best-fit narrative with references to the original source used.

Index to Eyewitnesses: Americans

| Eyewitness | Source (See Bibliography) |

| Brown, Solomon | Brown p123-130 |

| Deposition of 34 Eyewitnesses | Force p492-3 |

| Deposition of 14 Eyewitnesses | Force p492-3 |

| Clark, Reverend Jonas | Clark p1-7 |

| Douglass, Robert | Ripley 1832 p35 |

| Draper, William | Force p495 |

| Fessenden, Thomas | Force p495-6 |

| Harrington, Levi | Gordon p1, Harrington p1 |

| Leonard, George (Wounded Militiaman) | French 1932 p57-58 |

| Locke, Amos | Phinney 1825 p38-39; |

| Mead, Levi and Harrington, Levi | Force p494-5 |

| Munro, Orderly Sergeant William | Force p493-4, Phinney p33-35 |

| Munroe, Ebenezer | Phinney 1825 p36-37 |

| Munroe, John Jr. | Force p493-4, Phinney p35-36 |

| Munroe, Nathan | Phinney 1825 p38 |

| Parker, Captain John | Force p491 |

| Revere, Paul | Revere p106-111, Gordon p1 |

| Robbins, John | Force p491 |

| Sanderson, Elijah | 1775: Force p489, 1824: Phinney p31-33 |

| Smith, Timothy | Force p494 |

| Tidd, Benjamin and Abbot, Joseph | Force p492 |

| Tidd, Lieutenant William | Force p492-3, Phinney p37-38 |

| Underwood, Joseph | Phinney 1825 p39 |

| Willard, Thomas Price | Force p489-90 |

| Winship, Simon | Force p490 |

| Wood, Sylvanus | Ripley p35-37 |

Index to Eyewitnesses: British

| Name | Source (See Bibliography) |

| Barker, Lieutenant John | Dana p31-32 |

| Bateman, Private John | Force p496 |

| DeBerniere , Ensign Henry | DeBerniere p214 |

| Gould, Lieutenant Edward | Force p500-1 |

| Lee, Samuel (Soldier’s Talk) | Gordon p1 |

| Light Infantry Private Soldier | Willard, p198 |

| Lister, Ensign Jeremy | Murdock 1931 p17-24 |

| Marr, Private James | Gordon p1 |

| Pitcairn, Major John | French p52-54 |

| Smith, Lt. Colonel Francis* | French p62-63 |

| Soutar, Captain William | Hargreaves p219 |

| Sutherland, Lieutenant William | Murdock 1927 p13-24 |

* While Lt. Colonel Smith was not present for the fight, his statement is included since he claims to have talked to all the officers present. It largely aligns with Pitcairn’s report, but includes a few distinct details.

Bibliography

Beck, Derek W.: “Who Shot First? The Americans!”, Journal of the American Revolution, 16 April 2014

Brown, G. W.: “Sketch of the Life of Solomon Brown”, Lexington Historical Society Proceedings, Vol II, 1900

Clark, Rev. Jonas: “19 April 1776 Sermon”, Appendix, p1-7, 1776

Dana, Elizabeth et al.: “The British in Boston”, 1924

DeBerniere, Henry: “Narrative, &c.”, Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. IV of the Second Series, 1816, p205-215

Force, Peter: “American Archives”, 4th Series Volume II, Undated

French, Allen: “General Gage’s Informers”, 1932

Galvin, John R.: “The Minute Men”, 2nd Edition, 1989

Gordon, Rev. William: “Letter to Englishman”, 17 May 1775, Reprinted by the Philadelphia Gazette 7 June 1775 (Retrieved from Newspapers.com Feb 2024)

Hargreaves, Reginald: “The Bloodybacks”, 1968

Harrington, Levi: “Account of the Battle of Lexington”, Manuscript available from Lexington Historical Society, 1846

Murdock, Harold: “Late News of the Ravages”, 1927

Murdock, Harold: “The Concord Fight”, 1931

Phinney, Elias: “History of the Battle at Lexington”, 1825

Revere, Paul: “A Letter from Col. Paul Revere to the Corresponding Secretary” [The “Belknap Letter”], Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society For the Year 1798, Series 1, Volume 5, 1798 [Reprinted 1835], p106-111

Ripley, Ezra: “History of the Fight at Concord”, 2nd Edition, 1832

Tourtellot, Arthur B.: “Lexington & Concord”, 1959

Varney, George: “The Story of Patriot’s Day”, 1895

Willard, Margaret Wheeler: “Letters On the Revolution”, 1774-1776, 1925

Footnotes

[1] Examples: Gordon, 1775; Clark, 1776; Phinney, 1825; Boston News Letter, 1826; Everett, 1835; Frothingham, 1851; Varney, 1895; Coburn, 1912; Galvin, 1989;

[2] Examples: Tourtellot, 1959; Hackett-Fischer, 1993; Daughan, 2018; Journal of the American Revolution, “Who Shot First? The Americans!”, 2014. Admittedly some of the early versions may have only hinted at the “apologist” narrative, but they certainly set the trend in motion.