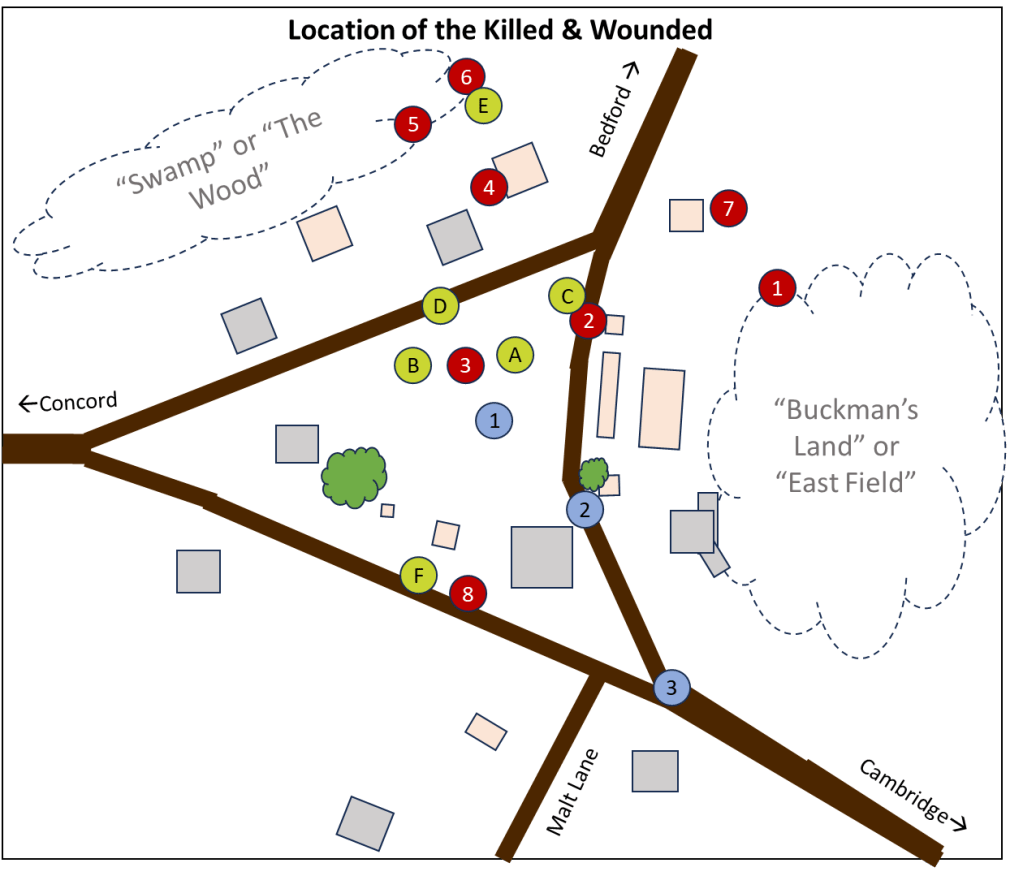

In the diagram below of Lexington Common, red markers note the location of the bodies of the killed provincials were found. Yellow markers indicate the approximate location of some of the wounded (reports said as many as nineteen were wounded, but only eleven are documented and only five can be positioned). Blue markers indicate the location of wounded British. For details on the reconstruction of the map itself, click here.

Provincials Killed (Red Markers)

1. Asahel Porter

Asa Porter was an unarmed noncombatant found dead after the fight. He had been taken prisoner by the British on their march up. Accounts differ on whether he was shot trying to escape or mistaken for a deserter, but are consistent in that he was shot running away from the British line. For more discussion on why he was shot, read this.

As for where he was shot, John Munroe Jr.’s 1824 account states only:

Asahel Porter . . . was shot within a few rods of the common.

Historian Silas Dean, who knew Porter’s widow, said this:

On getting over a wall a short distance off [the British line], he was fired upon and received his death wound.

Levi Harrington’s 1846 account adds a little more information:

Israel [Asahel] Porter. . . was killed and his body was found close by the stone wall below Merriam’s garden [Buckman’s in 1775], east of the meetinghouse.

We can only guess the extent of Buckman’s garden, but it needed to provide fresh food for both family and tavern guests, so it might have covered an acre or more. “Below” could mean either elevation or direction.

Supporting the idea of a large garden is Amos Lock’s 1825 account, which says that, on hearing firing on the common (where he and his cousin Ebenezer had just been):

We immediately returned, coming up towards the easterly side of the common, where, under the cover of a wall, about twenty rods distant from the common, where the British then were, we found Asahel Porter, of Woburn, shot through the body; upon which Ebenezer Lock took aim and discharged his gun at the Britons.

Notably, Amos Lock was the only one of the four who definitively saw where Asahel fell. Twenty rods equates to about 110 yards.

Amos and Ebenezer Lock were returning home when they heard the shots, lived northeast of the common, and are said to have approached from that direction (perhaps a bit south of modern-day Adams Street). This supports the idea that Asahel made it some distance from the British before he fell. Had Porter fallen due east of the meetinghouse, directly east of Buckman Tavern, the Locks arguably would not have come upon him.

Synthesizing the four accounts, we might conclude that a stone wall ran along the north end of Buckman’s garden, and that this was the stone wall Asahel Porter was climbing over when he was shot, and the Locks were approaching the common along the same wall when they found him.

2. Robert Munroe

Levi Harrington’s 1846 account says:

Ensign Robert Munroe was killed while making his escape. He was found dead where Merriam’s barn now stands, a few rods N. E. of the meetinghouse. He was evidently shot while in the act of climbing the stone wall.

This is supported by John Munroe Jr.’s 1824 account, which says his father was found “near the place where our line was formed.”

Given the location, Ensign Robert appears to have fallen victim to the first lethal British volley or, if he lingered more than most of Parker’s left wing, immediately afterward.

3. Jonas Parker

John Munroe Jr.’s 1824 account says:

After the second fire of the British troops, I distinctly saw Jonas Parker struggling on the ground, with his gun in his hand, apparently attempting to reload it. In this situation the British came up, run him through with the bayonet, and killed him on the spot.

Similarly William Munroe’s 1825 account says:

When the British troops came up, I saw Jonas Parker standing in the ranks, with his balls and flints in his hat, on the ground, between his feet, and heard him declare, that he would never run. He was shot down at the second fire of the British , and when I left, I saw him struggling on the ground, attempting to load his gun, which I have no doubt he had once discharged at the British. As he lay on the ground, they run him through with the bayonet.

Both John Jr. and William mentioned a first volley that hit no one, presumably warning shots overhead or powder only. The “second fire”, therefore, was the first barrage of guns aimed at the provincials.

Levi Harrington’s 1846 account adds:

Jonas Parker was mortally wounded, a ball passing through his body, but resolving to sell his life as dearly as possible. . . he attempted to load and fire again. . . and [the British] put an end to his life with their bayonets.

It’s not clear who actually saw the bayoneting, but the witnesses place the body on the green pierced by both a musket ball and a blade. Presumably, some observers did witness the event since all statements specify a soldier’s bayonet and not, say, an officer’s sword.

The circumstances of Jonas Parker’s death serves to highlight the British state of mind. Why didn’t they simply take his gun? He presented no threat if it wasn’t reloaded, and he’d already been shot.

4. Jonathan Harrington Jr.

Levi Harrington’s 1846 account says:

Jonathan Harrington, after leaving the common went to his house, a few rods north, took his wife and child by the hand and was leaving the house by the back way when he was discovered by the British, who fired and killed him. (Perhaps he was running towards the house when he was killed). His wife saw him fall. He was found near his barn, where the Bedford Road now is.

John Munroe Jr.’s 1824 account says Jonathan Harrington was found “near the place where our line was formed.” Hudson’s 1868 History of Lexington says Harrington was “killed on or near the Common”.

Canavan (Vol 1, p120) gives this version:

When the British fired, his wife saw him fall and start up with blood flowing from his breast. He stretched out his hands to her, fell again, and crept towards the house. She ran out to meet him and he died at her feet.

Levi’s account raises the question of whether Jonathan left the militia line the instant Parker ordered the militia to disperse (or even earlier) to protect his family. He arguably would not have tried to leave the house once the shooting started, implying he had already returned home and, after telling his wife they needed to leave, was outside by the barn (fetching a horse, for example). The first lethal volley might have killed him. Or he was in the barn at the time of the barrage and killed by scattered fire while running back to the house.

5. Samuel Hadley and 6. John Brown

Levi Harrington’s 1846 account says:

Isaac Hadley and John Parker [presumably Samuel Hadley and John Brown] were found at the edge of the swamp, near where J. D. Sumner’s ice house now stands. They were killed while running from the common.

John Munroe Jr.’s 1824 account says:

Samuel Hadley and John Brown were killed after they had gotten off the common.

I could not find Sumner’s ice house on any map, but any structures built near the swamp would have arguably been along the new Bedford Street.

7. Isaac Muzzy

Levi Harrington’s 1846 account says:

Isaac Muzzy was found dead back of Vile’s shoe manufactory, near where the academy now stands, north of the meetinghouse.

This is the only mention I could find suggesting Viles Shoe Manufactory existed at the time of the fight, which future research would hopefully corroborate. According to the town website, the Lexington Academy stood at 1 Hancock Street, which allows for placement of Muzzy’s body.

8. Caleb Harrington

Ensign Henry DeBerniere’s narrative says:

Some of them [the rebels] got into the church and fired from it, but were soon drove out.

Joshua Simonds account, related by descendant Eli Simonds, states:

I heard the order “Clear that meetinghouse!”Levi Harrington’s 1846 account says:

Levi Harrington’s 1846 account says:

Joshua Simonds, Caleb Harrington, and Joseph Comee were in the meeting house when the firing commenced. Harrington and Comee came out and ran towards the Munroe house. Harrington was killed at the west end of the meetinghouse.

John Munroe Jr.’s 1824 account says:

Caleb Harrington was shot down on attempting to leave the meeting-house.

Taken together, Caleb fired from the meetinghouse, then was killed attempting to flee. He and Comee may have been the source of the shots that wounded Major Pitcairn’s horse (see below).

Wounded (Yellow Markers)

At least eleven men were wounded during the fight, some slightly, others crippled for life. Ensign DeBerniere, a young British officer serving as a guide, placed the number of dead at fourteen, which suggests some he thought were killed were in fact only severely wounded (badly enough to lie immobile on the ground while the British ate breakfast).

The first figure of provincial wounded recorded in writing comes from a loyalist, George Leonard, who incognito met a wounded militiaman on the road. Leonard said the militiaman told him the British “killed eight and wounded nineteen”. That afternoon a report reached John Andrews in Boston that eight were killed and fourteen wounded.

The names provided below are the eleven documented (ten by Reverend Clark plus William Diamond). Presumably any others were either slightly wounded or altogether exaggerated.

A. John Robbins

In his 1775 deposition, John Robbins stated:

I being in the front rank. . .we received a very heavy and close fire from them, at which instant, being wounded, I fell and several of our men were shot dead by one volley.

Robbins does not say whether he was dispersing. If so, he may have been a few yards behind the initial line when hit. Of those wounded who were later compensated by the Provincial Congress, Robbins received the most: 23 pounds for lost time and expense plus 13 pounds annually afterward.

His statement that “several” men were shot dead by one volley appears limited to Robert Munroe and Jonas Parker, who was mortally wounded. Jonathan Harrington Jr is a possible third (by his barn), but it seems more likely he was shot shortly afterward.

B. Ebenezer Munroe

John Munroe Jr’s 1824 statement says:

After the first fire of the regulars, I thought, and so stated to Ebenezer Munroe, Jun., who stood next to me on the left, that they had fired nothing but powder; but on the second firing, Munroe said, they had fired something more than powder, for he had received a wound in his arm.

Ebenezer’s 1825 statement, which omits the powder-only volley, merely says:

After the first [lethal] fire, I received a wound in my arm.

So, Ebenezer was hit by the same volley that wounded John Robbins and killed two or three others. His wound was slight enough that he is said to have ridden from town to town to show it as proof of the British attack. The Provincial Congress awarded him 4 pounds in compensation.

C. William Diamond

M. J. Canavan [Vol 1, p138] says this about Parker’s fife and drummer:

Jonathan Harrington [3rd]. . . took his fife and light gun and went to the Common. When the British fired the drummer and he [Jonathan Harrington, the fife] jumped over Buckman’s wall and got out of range. The drummer’s hand was bleeding and they saw that the end of his little finger was shot off.

The drummer was 16-year-old William Diamond. Canavan does not say how he came upon the story but the most likely source was the fife himself, who lived until 1854 and is the focus of the tale. No record exists for any claim for the slight wound.

D. John Tidd

John filed a petition with the Provincial Congress stating he:

Received a wound in the head (by a cutlas) from the Enemy, which brought him (senseless) to the ground at which time they took from him his gun. . .

Hudson, in his 1868 History of Lexington, says of Tidd:

He was among the last to leave the ground, and was pursued by a British officer on horseback and struck down by a sword; and while he was senseless upon the ground, the British robbed him of his arms and left him for dead.

The Provincial Congress awarded Tidd four pounds. It’s not clear whether Hudson had heard Tidd left the field last or assumed it from the nature of the blow. It’s possible he was dispersing and struck by one of the officers British Lieutenant William Sutherland says “rode amongst” the militia in an attempt to surround them.

E. Prince Estabrook

Thomas Meriam Stetson, in the Opening Address of the Lexington Centennial Celebration 19 April 1875, stated (evidently pointing as he did):

There fell John Brown, battling by the wounded slave Prince Esterbrook.

Ellen Chase’s 1910 narrative relates it this way:

Brown’s body lay beside the wounded slave, “Prince” Esterbrook

It’s possible Stetson was merely waxing poetic. However, perhaps Stetson knew a since-lost detail that places Prince near John Brown, who Levi Harrington says was found near the swamp’s edge behind the Harrington homes.

Note: Prince appears on Lexington tax records in 1771, suggesting he was a free man at the time of the fight.

F. Joseph Comee

Numerous accounts state Joseph Comee was wounded in the arm running from the meetinghouse to Marrett Munroe’s. He did not fall, but kept running through Munroe’s house and over the hill behind.

Citing a 19 April 1875 Boston Journal article, which I could not easily locate, Ellen Chase describes the wound:

in his left arm, “having the cords and arteries cut in such a manner as to render his arm entirely useless for more than three months.”

The Provincial Congress later awarded him twelve pounds in compensation.

Others Wounded

Nathaniel Farmer, Thomas Winship, Jacob Bacon, Solomon Pierce, and Jedediah Munroe were also wounded, some severely, but I found no information on where they were standing (or running) when hit. Judging by the awards from the Provincial Congress, Farmer’s wound was as serious as Comee’s, followed by Bacon and Pierce. Munroe was killed in the afternoon, so his wound must have been slight. Winship’s wound appears to have gone undocumented.

Near Misses

Ebenezer Munroe Jr.’s 1825 account says that, soon after the shot that wounded him, two balls almost hit him as he ran from the line:

As I fired, my face being toward them, one ball cut off a part of one of my ear locks, which was then pinned up. Another ball passed between my arm and my body and just marked by clothes.

G. W. Brown’s sketch of his father, Solomon Brown, says :

Solomon Brown went to the right across the Bedford Road and jumped over a stone wall. As he landed upon the ground a ball passed through his coat, cutting his vest. Another about the same moment struck the wall.

Elijah Sanderson said this about the balls striking the wall by Solomon Brown:

I saw them [the British] firing at one man, Solomon Brown, who was stationed behind a wall. I saw the wall smoke with the bullets hitting it.

The British Wounded (Blue Markers)

Two British soldiers were wounded. So was Major Pitcairn’s horse.

1. Private Johnson, 10th Light Infantry

In his report to General Gage, Pitcairn mentioned a soldier in the 10th Light Infantry was wounded during the fight, but provided no details.

In his 1780s memoir, Ensign Jeremy Lister, a replacement officer in the 10th Light Infantry that morning, said:

We had one man wounded of our company in the leg. His name was Johnson.

(I recall the soldier’s name might have appeared on army rolls as Johnston, not Johnson, but I can’t find the reference at present.)

Ensign DeBerniere, who was with the detachment as a guide, stated in a narrative prepared shortly after the fight:

Major Pitcairn. . . ordered our light infantry to advance and disarm them, which they were doing. . .[shots fired]. . . There was only one of the 10th light infantry received a shot through his leg

Since DeBerniere belonged to the 10th, we can interpret “our” light infantry to mean the 10th light infantry was the front company closest to the provincial line. Sutherland’s report names Captain Parsons of the 10th and Lieuts Gould and Barker of the 4th as officers who could corroborate his version of the fight. I can’t find evidence of whether they lined up on the green one after the other or side by side.

Whether Johnson was hit immediately (by Jonas Parker or Ebenezer Munroe) or not is unknown; He might have possibly been wounded later chasing after the militia.

2. Major Pitcairn’s Horse

Major Pitcairn’s report to Gage says:

. . .my horse was wounded in two places from some quarter or other. . .

Ensign Lister’s memoir corroborates Pitcairn’s statement with:

Also Major Pitcairn’s horse was shot in the flank.

Many retellings place Pitcairn at the front of the advancing troops, but a new paper suggests provincial eyewitnesses attributed the names they read in the newspapers to the wrong officers they saw on the field. If so, the Marine major remained by the meetinghouse and the shots meant for him that instead wounded his horse most likely originated nearby, e.g. Joseph Comee and Caleb Harrington in the meetinghouse or, somewhat less likely but possible, an unknown shooter at the back door of Buckman tavern.

3. Second Unidentified Private Soldier

Abijah Harrington, a 14-year-old who arrived at the common shortly after the fight, gave this statement in 1825:

At a distance of about ten or twelve rods below the meetinghouse, where I was told the main body of their troops stood when they were fired upon by our militia, I distinctly saw blood on the ground in the road and the ground being a little descending the blood had run along the road about six or eight feet. A day or two after the 19th, I was telling Solomon Brown of the circumstance of my having seen blood in the road and where it was. He then stated to me that he fired in that direction and the road was then full of regulars, and he though he must have hit some of them.

This appears to have been the shot G.W. Brown says his father took from the front door of Buckman Tavern a few minutes into the fight.

Elijah Sanderson’s 1824 account says:

I saw the blood where the column of the British had stood when Solomon Brown fired at them.

If the 10th light infantryman was wounded on the common, then whose blood did Abijah Harrington and others find in the road below the meetinghouse?

Ebenezer Munroe’s 1825 account includes this statement:

I believed at the time that some of our shots must have done execution. I was afterward confirmed in this opinion by the observations of some prisoners, whom we took in the afternoon, who stated that one of their soldiers was wounded in the thigh, and that another received a shot through his hand.

This appears to be the only reference to a 2nd wounded British soldier.

Notably, it’s possible (if unlikely) Solomon Brown wounded both soldiers, as he is said to have fired both from Buckman’s stone wall onto the common and also from Buckman’s front door at the rear column of soldiers in the road. There is, however, some evidence another provincial fired from Buckman’s front door before him, and several others stated they fired on the common, so its not definitive either of Brown’s shots were the ones that found their mark.

A Lethal Volley Under Orders

Some modern scholars have argued British soldiers only fired “without orders”, even though numerous witnesses (including British Captain William Soutar) said otherwise. The recorded locations of killed and wounded militiamen supports Soutar’s statement that the van light infantry company “formed and fired” in response to a shout from the leading officers.

Ebenezer Munroe Jr was wounded on the west wing at almost the same moment Robert Munroe was killed on the east side, with Jonas Parker and John Robbins shot down in between. More shots hit Buckman’s wall and blew off the drummer’s fingertip. The dispersion suggests the entire front rank of the British troops fired simultaneously.

Also, smoothbore muskets were notoriously inaccurate. Many balls flew high or into the dirt. So the number of killed and wounded suggests many more guns were fired than merely those that “did execution”. The front light infantry company in the British line had 30-35 muskets. Most or all of whom must have fired to hit five or more militiamen.

Which begs the question: Why would so many professional soldiers fire at once, except under orders?

Wild “Too Great Warmth” Afterward

The dispersion of the dead off the common supports British Lt. Barker’s statement that, once the shooting began, the regulars were “wild”. The militia reported they fired at any provincial with a musket and even those without were in danger of losing their lives.

Lt. Sutherland reported:

Col Smith and Major Pitcairn regretted in my hearing the too great warmth of the soldiers in not attending to their officers and keeping their ranks

Harmless Shots Across the Swamp

Most of the militia are said to have regrouped across the swamp north of the common, which the British evidently did not attempt to cross. Firing took place, but at a great distance. No one was reported killed, although its possible a militiaman or two were wounded by lucky shots.

Sources

Brown, G. W., “Sketch of the Life of Solomon Brown”, Lexington Historical Society Proceeding, Vol II, 1900, p126-7.

Simonds, Eli, “Echoes of the Lexington Belfry”, Boston Globe, 17 July 1895, p6.

Phinney, Elias, “History of the Battle of Lexington”, 1825.

Harrington, Levi, “Account of the Battle of Lexington”, 1846, Copy courtesy of the Lexington Historical Society.