One of the 19 April 1775 stories retold in West Cambridge—now Arlington, Mass—describes a British halt outside Cutler Tavern where a man named “Tidd” slept in a hired girl’s room. Research shows he was probably 21-year-old John Tidd, a journeyman blacksmith from Lexington.

The Story

An 1864 version of the British halt [Smith, p18-19] says:

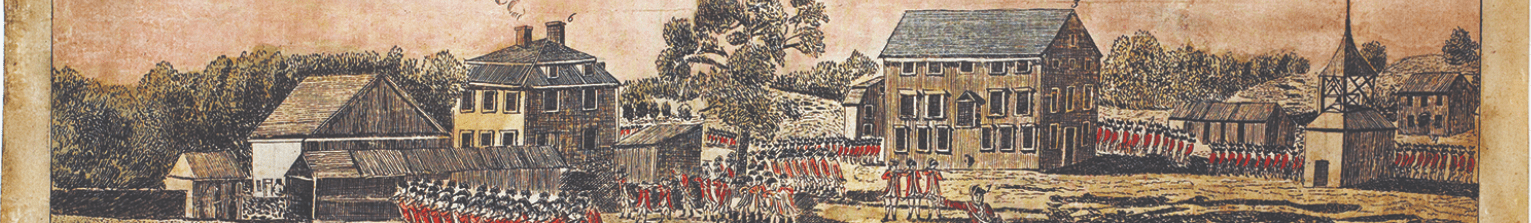

They [the British] paused a moment at the centre of the town. . . Mr. Cutter, who lived in the house now the westerly end of the upper tavern, looked around for his gun as he saw the soldiers open his barn doors and look at his favorite horse, but he had lent it the day before, much to his wife’s joy.

A more detailed account [Brown, p2] says the tavern keeper, William Cutler (not Cutter), actually slept through the entire British halt. This version, which comes from Cutler’s daughter, Rebecca:

. . . the yard was full of redcoats. They had started for Concord and this was their first halt. Everything was still; there was no noise except from their accoutrements. My mother [William Cutler’s wife] shut the light into a cupboard and went into an adjoining room, where the hired girl and her beau were sitting up. She found them side by side, both fast asleep.

She shook the man and told him to hold the latch, but not to slip the bolt, for fear of being heard. After almost twenty minutes of perfect quiet, the British went to the barn, as was supposed, to take the horses. There were four horses in the barn but they were unmolested.

My father was asleep, and mother had been particularly careful that he should not be wakened until the troops were out of the way. When he was roused, he called for his gun, declaring he would shoot the first man who took a horse from his stable. The gun had been lent a few days before, or serious consequences might have resulted. He went out immediately to ascertain he amount of mischief.

While in the yard, four of the officers came riding back, probably to see if anyone had been aroused, and asked for a drink of water. My father sent the man, Tidd [the hired girl’s beau], to bring water while he conversed with the officers upon the weather and where they were riding. They replied they were out to see the country. To his question, why they took the night for such an excursion, they curtly replied, “It’s none of your business, go to bed and get your rest when you can have a chance” and rode off toward Lexington.

It’s curious the man is referred to only as “Tidd.” Did Francis Brown M.D., who authored the article, know Tidd’s first name but discretion prompted him to leave it out of print. Did Rebecca Cutler (married names Tufts and then Russell) remember the surname of an employee’s boyfriend so many years later, or did Brown learn it some other way?

A records review shows only one Tidd man living in West Cambridge in 1775: 21-year-old John Tidd, a journeyman blacksmith and corporal in Benjamin Lock’s company of militia.

John Tidd Disambiguation

There were three men named “John Tidd” on 19 April militia rolls, all 2nd cousins to each other, so identifying the family of the West Cambridge man took a little effort.

The first John Tidd, the 25-year-old son of Lexington yeoman Joseph and Dorithy Stickney Tidd, belonged to Parker’s Company. He was wounded in the fight on Lexington Common.

The second was the 23-yr-old son of Medford shopkeeper Ebenezer and Elizabeth Fortner Tidd. When Ebenezer died in 1765, this John Tidd chose his uncle, Jonathan Tidd of Woburn, as guardian. On reaching adulthood he settled in Westford, where he is listed in the militia in 1775 and married in 1776 and again in 1780.

The third John Tidd, who lived in West Cambridge, was evidently the 21-year-old son of Amos and Elizabeth Smith Tidd and a nephew of Lexington’s Lieutenant William and Samuel Tidd. He was baptized on 15 July 1753, the second of seven boys.

Can we be sure the West Cambridge man was the Lexington-born son of Amos Tidd? The best link is a letter from Susannah Sanford, who was a girl in Hopkinton Mass in 1779 when John Tidd came home from the army in poor health and resided with his father there, who was then living in a part of the same house. She did not know the name of the father, but Amos Tidd was the only living father of any of the three John Tidds. So, the John Tidd who married Abigail (Susannah attended their wedding) was the son of Amos.

Other circumstantial evidence supports this conclusion. The West Cambridge John Tidd lived with Lexington-born Solomon Bowman, and his widow’s pension application lists a Lexington man as kin. The Westford John Tidd, by contrast, served with Woburn men in 1775 where guardian Jonathan Tidd was from, so more likely the son of Jonathan’s brother Ebenezer.

John Tidd, Son of Amos

John’s father, Amos, worked on the Lexington parsonage farm for much of the 1760s. Clark’s journal shows numerous dates and payments to Amos, along with entries like “Mr. Tidd’s child scalded.” Whether this was young John or one of his siblings is uncertain, but it stands to reason John would have spent much of his early childhood at the parsonage and the Tidd farm up the road. He knew Reverend Clark and his family as well as many of the young men in Parker’s company: Joseph Fisk, Joseph Comee, Ebenezer Munroe Jr, Moses Harrington, and Eli Burdoo to name a few.

Amos Tidd’s son probably attended grammar school with this young men but moved as a teenager. An 1839 letter from Charles Cutter of West Cambridge says:

John Tidd served his apprenticeship at the blacksmith’s business with Solomon Bowman in this town; and at the time of his enlistment [April 1775] was living with said Bowman.

Tidd’s master blacksmith, Solomon Bowman, was the son of Lexington’s Captain Thaddeus Bowman. John was almost 22 in April 1775, so had probably completed his apprenticeship the summer before.

Cutter’s letter is found in the war pension application filed by John Tidd’s widow, Abigail. Other documents in the collection state that John “was a blacksmith and worked as journeyman from place to place, in 1775 he was in West Cambridge”, that he served four tours in the Continental Army, that he married Abigail in 1780, and that William Chandler of Lexington was a relative. Chandler was the son of Ruth Tidd Chandler, John’s cousin.

The pension application appears to mistakenly conclude the West Cambridge John Tidd and the Westford John Tidd were the same person. They are not. The Westford man married twice and has many children on record there while the West Cambridge man, who married Abigail, moved to New York.

John Tidd on 19 April 1775

According to Brown, Rebecca Cutler said that, after the British left town:

My father then took one of his best horses and went out to arouse the people. The British had come so quietly that no one was aware of their movements. He went to the lower part of the town, and through what is now known as Belmont, Waltham, and Watertown.

In other words, Cutler rode away from the advancing British toward Cambridge, which makes sense since John Tidd was there to rouse the West Cambridge militia. Militia rolls [Smith, Cutter, and Coburn] show John Tidd was in Benjamin Lock’s company of West Cambridge militia where Bowman was lieutenant. Coburn lists Tidd as a corporal.

The logical move for Tidd would have been to run home to Bowman’s. He would have found Bowman awake; the militia lieutenant lived on the main road, had seen the regulars pass, and had even refused one a drink of water.

Smith says that, after the British marched through, Lock’s company mustered and marched to Lexington and worked “as sharpshooters” during the British afternoon retreat. Cutter [p56-7] argues they probably marched all the way to Concord and back with Thatcher’s “Old Cambridge” company.

However far they marched, they were reportedly back in West Cambridge when the British returned. Bowman fought one soldier hand to hand, knocking him down with the butt of his musket.

They might possibly have hidden in Bowman’s house waiting for the British to pass, as Mackenzie’s account states:

Some houses were forced open in which no person could be discovered, but when the column had passed numbers sallied out from some place in which they had lain concealed, fired at the rear guard, and augmented the numbers which followed us.

Where in a colonial house might armed men hide? Some period homes (including one I lived in) had a secret room built between the two chimneys accessibly only through a small door in the cellar. It’s easy to imagine Solomon Bowman and John Tidd barring themselves inside such a room while the British searched the house, then emerging afterward as Mackenzie describes.

One way or another, Bowman ended up firing on the rear guard and clubbing a regular with his musket. John Tidd was probably not far away.

John Tidd in the Revolution

John Tidd served in the Menotomy militia for the rest of 1775. They camped on Prospect Hill during the siege of Boston. Smith’s Address includes a Dec 1775 receipt for a pair of shoes John received from Captain Lock via Lt. Bowman.

He appears to have served again in 1776 from Holliston, where his father Amos then lived.

In 1777 he served from Lexington as “John Tidd Jr.” (“Jr” since cousin John Tidd, son of Joseph and Dorothy, was older). According to his pension file, he was told he would be a sergeant but, lacking the space, they offered him an artillery position. Abigail said they met in Hopkinton that year, so perhaps Amos had moved towns by then.

In 1778 he served again, discharged in early 1779. According to Susannah Sanford this was an early discharge due to poor health. He returned to Hopkinton where his father then lived, and married Abigail the following February (1780).

A note in his pension application says he served a total of 22 months in the Continental Army.

Later Years

John and Abigail had ten children. (The youngest, notably, is named Elbridge Gerry Tidd, so Hancock’s contemporary in the Committee of Safety must have made quite an impression.)

They resided in Hopkinton until the early 1800s, when they removed to upstate New York. Most of their children followed, some eventually settling in Michigan and Iowa.

John died in 1813. Abigail lived until 1854. Her frequent pension applications brought her a monthly stipend and 160 acres of bounty land.

Sources

Brown, Dr. Francis H., “The Passage of the British Troops Through Menotomy”, Arlington Advocate, 1 May 1875, p1: The most detailed description of the stop at Tuft’s Tavern run by Mr. and Mrs. William Culter. “hired girl”, “Tidd”, etc.

Clark, Reverend Jonas, Journal, 1766-1776: Numerous references to the employment of John Tidd’s father Amos through the late 1760s. “Mr. Tidd’s child scalded.”

Coburn 1912, 19 April Participants List, p76: John Tidd listed as a corporal in West Cambridge, Benjamin Locke’s company, along with Lt. Solomon Brown and Corporal Thomas Cutter, brother of Charles (see pension application). See also Smith’s 1864 Address.

Cutter, Benjamin and William R., History of the Town of Arlington, 1880, p59: “They entered the barn at the Cutler Tavern.”

French, Allen, A British Fusilier in Revolutionary Boston, 1926

Hudson 1868, G.R., p243-4: John Tidd 2nd son of Amos and Elizabeth Smith Tidd of Lexington, baptized July 1753. Amos was the son of Daniel and older brother of Lt. William Tidd.

Revolutionary War Muster Rolls: Three men living named John Tidd, all cousins, all in early 20s. In 1775, the John Tidd of Cambridge was 22 years old and stood 5ft 11in.

Revolutionary War Pension Applications (Ancestry.com) W.19.455, 1839, “Tidd John Abigail”: Abigail Tidd statement, letters from Susannah Sanford, Charles Cutter and others.

Smith, Samuel Abbot, “West Cambridge on 19 April 1775”, 1864, p18-19.