The post explores the role British flank guards might have played in the morning fight on Lexington Common on 19 April 1775.

A Few Known Facts

The existence of regular troops flanking the main column of Smith’s forward light infantry detachment (commanded by Major Pitcairn) is documented by Lieutenant William Sutherland, the volunteer from the 38th Foot who led the front party charged with capturing any provincials they met on the road.

Sutherland’s report of the events of 19 April 1775 states that, sometime after daylight, after waiting with prisoners for some time:

We turned back [down] the road we came and found the division, who had halted in consequence of the intelligence [that armed militia awaited them at Lexington] in order to make a disposition by advancing men in front and on the flanks to prevent a surprise.

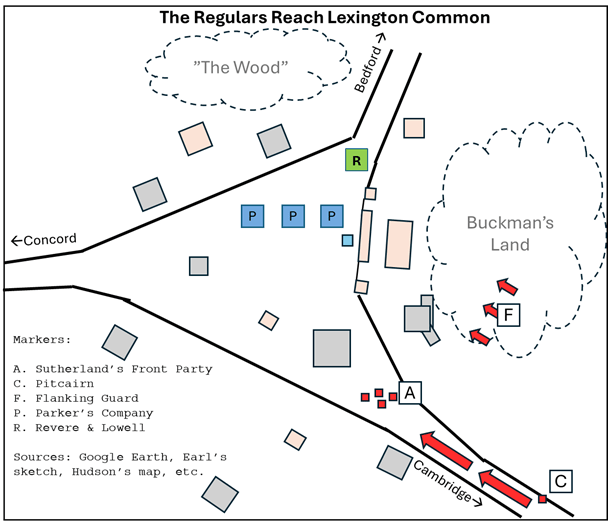

From Sutherland’s report [Murdock, p16], it seems clear that Major Pitcairn ordered flanking guards on both sides of the road and kept them there as they approached Lexington Common.

Which light infantry troops were deployed? Evidence suggests they were drawn from different companies, since Private James Marr of the King’s Own (4th) Light Infantry was part of the front party led by Lt. Sutherland of the 38th and Lt. Jesse Adair of the Marines. Perhaps the flank guard also consisted of mixed company.

What did the flank guard do? Light infantry flanking procedures are described in Townshend’s Rules and Orders for the Discipline of the Light Infantry Companies in His Majesty’s Army in Ireland [Smythies, p550]:

The Light Infantry must be careful not to fall into ambuscades when they are marching through a wood or any enclosed country and care must be taken to advance a guard, and to detach flanking parties, the flanking parties to march in front and the files to move at the distance of ten yards from each other, when either of these parties shall discover an enemy they are not to run into the main body but to take posts immediately and begin an attack . . .

From Townshend we conclude Pitcairn’s light infantry flanks were trained to deploy in two-man teams (files) spaced ten yards apart in a line at the front of the main column.

Whether they deployed on 19 April in according with Townsend’s instructions in unknown. Also procedures may have varied between regiments posted in Ireland (the 38th and 5th) and those, say, posted in Canada (the 10th), but it is hard to imagine how the instructions might have materially differed.

What Can We Deduce?

Since marching on a road was invariably easier than through woods and fields, we can imagine the flank guard had a hard time keeping up with Sutherland’s front party. Nevertheless, the final approach from Amos Muzzy’s house to Buckman Tavern supposedly included gardens, orchards and sheep pastures (not heavy woods, steep hills, or impassable rock piles) [Canavan, p123]. We can therefore assume the flanks approached Lexington Common with relative ease, arriving with or shortly after Sutherland, who reportedly first stopped 12-15 rods from Parker’s Company [Phinney, p35], evidently at the road junction below the meetinghouse.

Note: According to Sutherland, Pitcairn also deployed flankers to the left of the main column, who would have ensured no armed militia threatened from the south side of the road. Their role in the morning fight appears negligible, hence we ignore them.

The Right Flank Position

It’s notable that the right flank would have approached the rear of Buckman Tavern and the barn and stables east of Lexington Common, where they would have limited visibility of Parker’s Company. Captain Parker and his men may likewise have been unaware of their presence.

Their Orders

Communication between the main column and the flanks was limited to 1) signals, e.g. played on pipes and drums and 2) messengers. Its reasonable to assume they had different instructions from the main column, both intentionally and simply because they did not see and hear everything with the rest of the troops.

This idea raises several questions.

Did Pitcairn specifically order the flankers not to fire unless ordered (like he did the main column)? All reports suggest the main body of Pitcairn’s detachment did not load until just before reaching the common (after the flankers were ordered out). Likewise Pitcairn’s orders to hold fire unless ordered came then. Did those orders reach the flanks? Were their orders different?

Furthermore, did Pitcairn explicitly prohibit the flanks from discharging their arms if attacked? If not, it stands to reason that Townsend’s instructions to immediately engage the enemy would dictate their actions.

Finally, did the flankers have orders to shoot escaping prisoners and/or British deserters, as provincial stories imply?

Close To The Early Action

The answers to these questions, along with any role the flankers played in the fight, are undocumented. We can, however, make educated guesses on a few key points.

Sutherland’s Three “Rebel” Shots

First, the likely location of the flankers would have made it difficult if not impossible for the provincials to sneak up on Pitcairn’s men from behind the tavern. This casts doubt on Lt. Sutherland’s claim that “rebels” fired on them from the “end” of Buckman Tavern before the main engagement began. The shots he heard fired from that direction were more likely to have come from the flankers than anyone else.

Porter’s Run

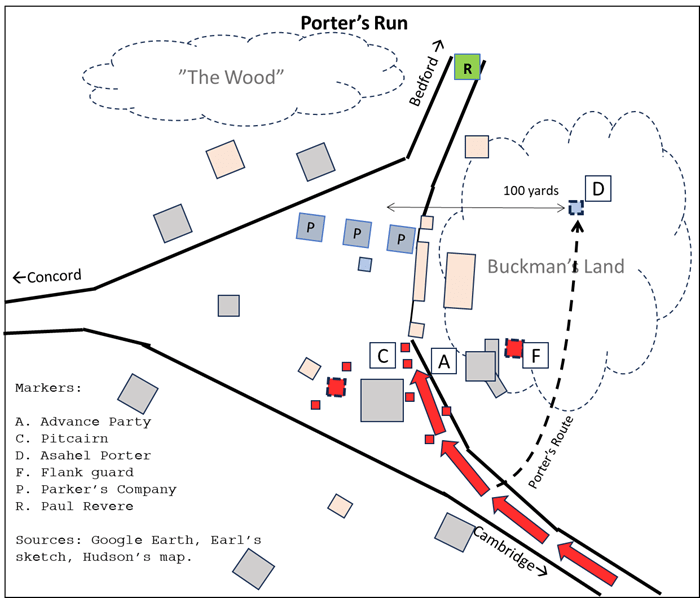

Second, troops guarding Pitcairn’s right flank behind Buckman Tavern would have been in position to observe released prisoners Josiah Richardson and Asahel Porter making their way across Buckman’s land toward the trail to Woburn.

According to sources, Porter was shot and killed while running from the main column, either for attempting escape [Phinney, p36] or because he was mistaken for a British deserter [Dean, p9]. Either way, Porter’s path home would have taken him north of the road, straight past the flank guard. Cousins Amos and Ebenezer Lock found Porter shot about a hundred yards (twenty rods) from the common [Phinney, p38-9] as they approached from their Woburn homes to the north [Lock, p68-72].

Given the distance from the main column, it seems most likely the closer flankers gunned him down.

The “First Shots”

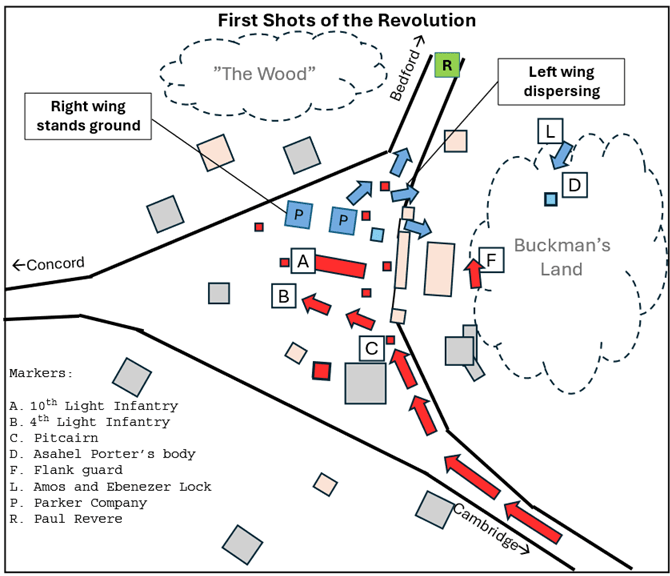

Did the flankers advance with the British on the common? This would be in accordance with their training to stay at the front of the column, which had pivoted north. So doing would place them even closer to the Lock cousins when Ebenezer fired at the British on the common [Phinney, p38-9], a shot his descendants claimed was the first of the revolution taken by an American [Bartlett, p1].

Townsend’s rules of engagement suggest the flankers were trained to immediately return fire. If they did, their gunshots may have tipped the already chaotic scene on the common over the edge into open battle.

Meanwhile, Parker’s men—Nathan Munroe and Solomon Brown, among others—were spilling over the wall onto Buckman’s land, seemingly unaware of the flank guard behind Buckman’s barn. The fact that no one was found dead on Buckman’s land supports the idea that the flankers had already discharged their weapons at the Lock cousins, and were in the process of reloading when the provincial retreat began.

While Parker’s men reportedly had time to fire a few shots, whatever reprieve they found proved short lived. Issac Muzzy was found killed behind Viles shoe shop north of Buckman’s land [Harrington, p3], either by the flankers or the King’s Own light infantry charging off the common.

What Is Certain

This is admittedly a great deal of deduction based on precious little evidence. All we know for certain is 1) British Lieutenant Sutherland reported a flank guard had been deployed, 2) our reconstruction of the fight places the early action off Lexington Common on Buckman’s land, precisely where the British right flank would have been, and 3) Light Infantry procedures dictated immediate engagement with an enemy.

All of which argues the flank guard played a role in starting the first fight of the American Revolution.

Sources:

Bartlett, Benjamin, “Ebenezer Lock”, Granite Monthly, 1890

Canavan, Michael J., The Canavan Papers, Vol 1, 1912

Dean, Silas, Brief History of Stoneham, 1870

Harrington, Levi, An Account of the Battle of Lexington, 1846

Locke, Herbert G., “Amos Locke”, Lexington Historical Society Proceedings, Vol 1, 1889

Murdock, Harold, Late News of the Excursions And Ravages of the Kings Troops, 1927

Phinney, Elias, Battle of Lexington, 1825

Smythies, Captain R. H. Raymond, Historical Records of the 40th (2nd Somersetshire) Regiment, 1894