A misread muster roll WITH aN untold story

The military record of Ensign Robert Munro, who fell in the first fatal volley fired by the British on Lexington Common on 19 April 1775, lies amidst considerable legend and lore. Some say he served with the famous Rogers’ Rangers. Others say he was the standard bearer at the 1758 Siege of Louisbourg, that he “watched the Indians” in 1762, and then, in his early sixties, served as an officer in the Lexington Militia Company in 1775.

Little of this is backed by surviving historical records.

There still exists, however, an old muster roll showing that Robert and Lexington men under his command fought in the bloodiest fight for the provincials in the entire French War: the 1755 Battle of Lake George.

The Early Life of Robert Munro

Robert Munro was born 4 May 1712, the sixth of nine children of Sergeant George and Sarah Munro. He grew up with numerous cousins in the sprawling “rope-walk” house of his Scottish-born grandfather, forced immigrant William Munro. Lexington had just become a town.

In 1737, Robert married Anna Stone. They lost their eldest son at age two, presumably to an unknown but fatal disease. Four later children, all born in the 1740s, lived to adulthood.

It’s reasonable to assume from Robert’s French War service as an officer that he gained some early soldiering experience with the provincial irregulars, perhaps during the 1740s conflicts with Spain (War of Jenkin’s Ear) and/or France (King George’s War). He was in his late twenties and early thirties during this period. Notably, a Munro cousin succumbed to disease on the trip home from Cuba in 1740, the same year Robert’s son, niece, and nephew all died within weeks. Perhaps young Robert was on the Cuba expedition, too, and carried the same fatal disease home with him

Unfortunately, since his name doesn’t appear in any known records before the 1754-1762 French War, we can only speculate.

Robert Munro in the French War

Lexington town historian Charles Hudson attempted to piece together Robert Munro’s French War a century after the fact. His published history [Hudson 1912, Vol II, p456] says of Robert:

He was a soldier in the French war, was the standard bearer at the taking of Louisburg in 1758, and was again in the service in 1762. He was also ensign of Capt. Parker’s company.

Separately, Hudson’s summary of Lexington’s French War service [Hudson 1912, Vol I, p413-19] includes “Ensign Robert Munroe” on the list of men serving in 1758 and “Robert Munroe” (no title) in 1762.

Is this information correct? The editors of the updated 1912 edition of Hudson’s history searched the surviving muster rolls and failed to find most names listed by Hudson for 1758, including Robert Munro.

There is some evidence Hudson used additional sources. For example, surviving billeting records (taverns invoiced the province for meals and lodging provided soldiers traveling to and from the New York battlefront, some of which survive in Massachusetts archives) show most names on Hudson’s list belonged to companies captained by Cambridge and Watertown men. Robert Munro’s name, however, I failed to find.

Another hint: Since Hudson lists Robert Munro as an ensign for 1758, he seems aware Robert served as an officer during the French War, at least for that year.

But let’s come back to that.

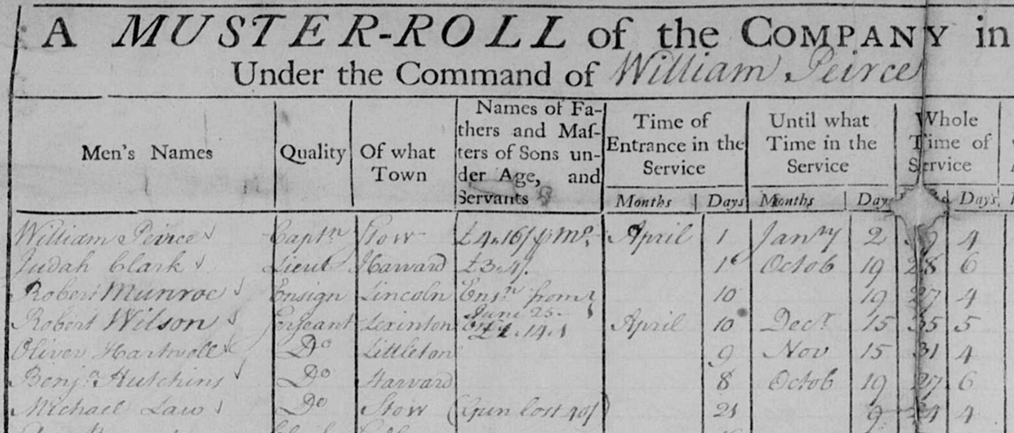

An Unread Muster Roll: Ensign Robert Munro of Peirce’s Company

While several attempts to confirm Robert Munro’s 1758 service have proven fruitless, Hudson’s 1912 edition includes this footnote:

Ensign Robert Munroe is credited, however, in 1756, to Lincoln.

Hudson does not mention any 1756 service for Robert Munro in his 1868 edition, so evidently overlooked the detail. Yet it appears the 1912 editors made a critical error: The roll was prepared 18 February 1756 for the preceding year. The men listed, including Robert Munro, all served in 1755.

With the corrected year, combined with other details preserved in the roll, a remarkable story snaps into focus.

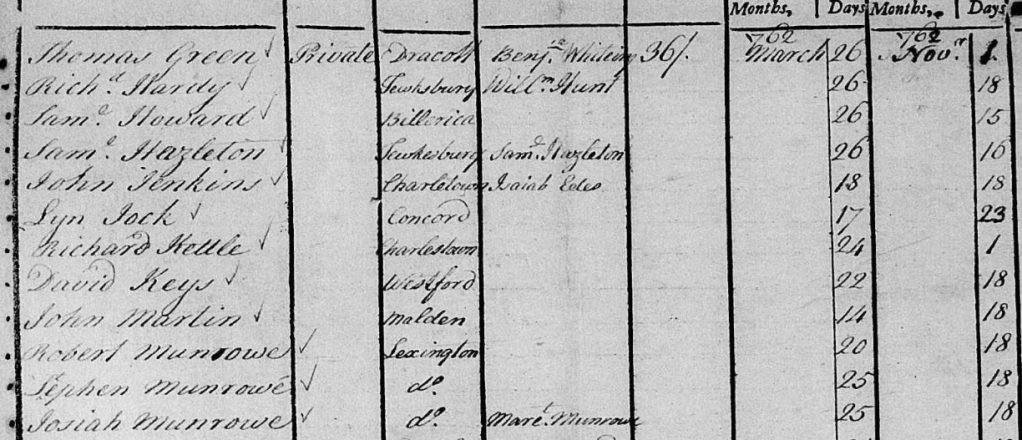

The muster roll in question survives today in volume 94, parchment 76 of the Massachusetts Colonial Records. I found a microfilmed copy at FamilySearch.org in the collection “v.93 Muster rolls (from p80); 1749-1755; v.94A – Muster rolls, 1755-1756; v.94B – Muster rolls (to p.419), 1755-1756)”, Image Group Number 7703435, image 830 of 1759.

Here is the upper left corner:

A few points to highlight:

- Munro was a new officer. The roll says that Robert Munro of Lincoln became the ensign of Captain William Peirce’s Company on June 25, so he received his commission that year.

- Peirce and Munro were family. Hudson’s history says Peirce was Munro’s cousin, the son of Joseph and Hannah Munro Peirce. Peirce was five years older than Robert. According to Hudson, Peirce lived in Lexington as a child and again as an adult before removing to Stow around 1743. The muster roll, as shown, places him in Stow in 1755.

- Munro recruited some soldiers. The 1755 journal of General John Winslow, who led a successful campaign in Nova Scotia that year, states that a prospective officer needed to raise 15 men for a company to earn an ensign’s commission. There are about that number of private soldiers from Middlesex towns Lincoln, Lexington, and Woburn. Since Peirce and his lieutenant were from Stow and Harvard (the latter in Worcester County), it appears Munro delivered on that requirement recruiting men from the towns near home.

- Lincoln, not Lexington? When William and Robert formed their company in the spring of 1755, the town of Lincoln had only existed for a few months. (The Massachusetts General Court approved in the creation of the town from parts of Concord, Lexington, and Weston during their 1754 session.) Perhaps Robert, like other Munros, owned land or even resided within the bounds of what became Lincoln at that time. Robert does not appear in Lexington town meeting records until the late 1760s, suggesting years with no involvement in Lexington affairs. He appears to have placed his Lexington land in trust for the benefit of his children (see the 1756 will of Robert’s father-in-law, Lexington selectman John Stone), so may have had no rights or obligations to the town during this time.

A possible Lincoln residence notwithstanding, Lexington appears to have continued to claim Robert as their own: A 1760 marriage record for Munro’s daughter, Anna, and Daniel Harrington contains no mention of her or her father “Ens. Robert” being from anyplace other than Lexington. And by 1767 Robert began to show up in Lexington town records, though he never held any town office. By 1775, it is generally believed he resided in Lexington’s Scotland neighborhood.

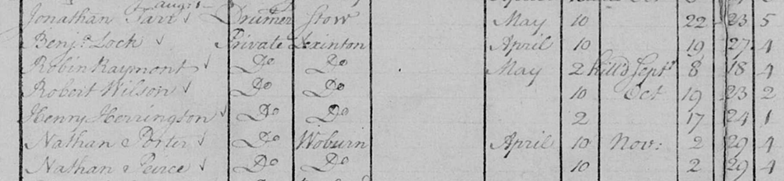

The Lexington Men In Peirce’s Company

In addition to Robert Munro as ensign, the muster roll for Peirce’s company includes five men from “Lexinton”: a sergeant, Robert Wilson, and four private soldiers: “Benj Lock”, “Robin Raymont”, “Robert Wilson”, and “Henry Herrington.”

Cross-referencing these names with Hudson’s history reveals the following: Benjamin Lock was the 20-yr-old elder brother of Amos Lock (who fought 19 April 1775). Raymont was probably the colored servant “Robin” that Jonathan Raymond left to his wife Charity in his will. Robert Wilson was probably the son of the sergeant in the same company. Henry Harrington, likewise, was the 18-year-old son of a man by the same name.

So, all four privates were young men.

The muster roll and other sources combine to show the dangers of military service. Raymont is reported “killed Sept 8.” Hudson says Benjamin Lock died of an unknown camp disease in Nov 1755, a month after his 19 Oct discharge. Hudson says one of the Wilsons (father or son is unclear) served again from Lexington in 1758; after that the family disappears from town records.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the roll is that Robin Raymont was not the only member of Peirce’s company reported killed September 8th, which leads to the obvious conclusion that Peirce’s company saw battle.

A big battle, it turns out.

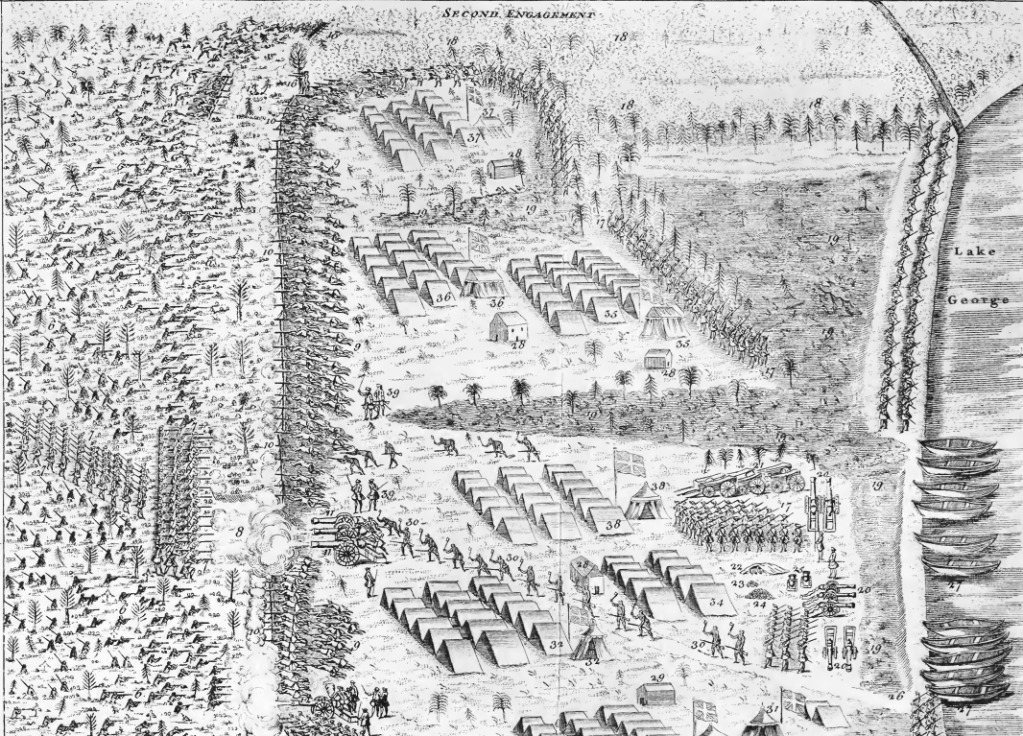

The Battle of Lake George

The four men of Peirce’s company “killed” on 8 September were Corporal Simon Peirce of Lincoln, Jonathan Barnard of Lincoln, Joseph Bulkley of Littleton, and Robin Raymont of Lexington. Since a fifth man, Asa Brewer of Sudbury, is listed “died” on 5 October, it seems clear the four listed “killed” all died in combat. The roll states “gun lost” for three of the four, supporting the idea they were killed in a place overtaken by the enemy, who stripped them of their arms.

What happened on 8 September 1755? This is the date of the Battle of Lake George, the first big encounter on the New York frontier between British and French forces. Fifteen hundred Massachusetts and Connecticut irregulars (not regular troops from Britain’s standing army), plus two hundred Mohawk allies, had camped on the banks of Lake George in upstate New York, a staging point for a planned attack on the French position at the other end of the lake.

The French came to them first. The battle—recounted in multiple sources including the diary of Lieutenant Colonel Seth Pomeroy and a published account by noncombatant Samuel Blodget—began with a morning ambush by French forces on a column of British provincials marching to Fort Edward, followed by an afternoon assault on the Provincial camp at the lake, during which the Massachusetts men gave and received heavy fire.

Colonel Seth Pomeroy said of it:

The Fire begun between 11 & 12 of ye clock and continued till near 5 afternoon ye most violent Fire perhaps yet ever was heard of in this country in any battle.

According to camp commander General William Johnson, the Massachusetts regiments took the worst of the onslaught. His report states:

The three regiments [of Massachusetts men] on the right supported the attack very resolutely, and kept a constant and strong fire upon the enemy.

The provincials and their native allies ultimately routed the enemy and captured the French commander. After a bloody third engagement that evening, the provincials declared the day a victory, but one costing hundreds of casualties. In total, one in five men were either killed or wounded.

Given the similar ratio of men reported killed on Peirce’s muster roll, we can assume the Lexington men held the camp’s western line with other Massachusetts companies, using a hastily constructed breastwork of fallen trees as cover for part of the afternoon, then jumping the breastwork to participate in the woods fighting (that claimed several lives at times when guns could be lost.)

No matter what else Robert Munro did during 1758 or any other year of the French War, the Lexington Militia Company had an experienced battle leader on their town common when the British regulars marched up on 19 April 1775.

What About Ensign Robert’s Later Service?

As stated earlier, Robert Munro’s 1758 service is unsupported by the surviving muster rolls, or any other contemporary document. Hudson’s note that Robert was “standard bearer at the taking of Louisbourg in 1758” is curious because that siege was conducted by the British Navy. The only New England troops present were supposedly four newly raised companies of Rogers Rangers. Major Rogers, in his journal, states himself that four of the five companies he raised in January 1758 went straight to Nova Scotia for the Louisbourg campaign under Amherst.

In a sketch of the life of Edmund Munro, another Lexington native who served as a Rogers Rangers adjutant, historian Michael J. Canavan [Canavan, Vol II, p236] says:

Four companies [of Rogers’ Rangers] were sent to Louisberg under Amherst. And Edmund’s cousin, Robert Munroe, was probably in one of these companies.

It’s unclear whether Canavan, who did his research after Hudson, arrived at this conclusion from some now unavailable source or else from deduction based on 1) Hudson statement that Robert was at Louisbourg in 1758 and 2) Knowledge that the only provincials at Louisbourg in 1758 were Rogers’ Rangers.

Is there any evidence Munro was in the Rangers at all, much less in one of these companies?

Robert Munro, Possible Ranger

The organization of British forces changed considerably after 1755. In that year, Captain Peirce formed his company under the authority of the Governor Shirley of Massachusetts. Peirce and his officers (including Munro) received commissions signed by the royal governor, who also happened to be leading a military campaign.

After 1755, disagreements between Shirley of Massachusetts and the new commander of British forces in North America, Lord Loudon, limited the involvement of provincial troops. The 3000 troops raised by Massachusetts for the 1756 campaign waited in vain for orders. Frustrated by the waste, in 1757 Massachusetts raised only 1800. So, while Peirce and Munroe may have raised another company for 1756, they likely did not for 1757.

Meanwhile, Lord Loudon’s second in command, Abercrombie, engaged with New Hampshire native Robert Rogers to build up several companies of rangers. One company in 1756 was quickly followed by a second. Two more were added by 1757, including one that came under the command of a Littleton man: Captain Charles Bulkeley. Men for Rogers’ first two companies were mostly from NH, but by 1757 Rogers was also recruiting in Massachusetts.

Names appearing in Bulkeley’s August 1757 roll [Rogers, p27] match men born in Lexington who had moved to the Littleton area: Benjamin Bridge, Josiah Hastings, Abraham Munroe, Abraham Scott, and possibly others. Bulkeley made his will that year in Halifax, so the men probably served in Nova Scotia.

Further strengthening the connection between Lexington and the Rangers: Captain Peirce’s company included two Littleton men named Bulkeley, Joseph (who was killed in the Lake George fight) and Peter (who deserted). Joseph, Peter and Captain Charles were all sons of Joseph Bulkeley of Littleton, b 1712, 1715, and 1717 respectively [Jacobus, p148]. Charles made Peter his sole heir in his 1757 will. Of the three, only Peter survived the war, married, and raised a family in Littleton. Joseph and Peter would have been 40 and 38 in 1755 when they were private soldiers in Peirce’s company, only a few years younger than Robert Munro.

Given these connections, Robert Munro might have been the first in the Lexington area to hear about Rogers Rangers. The Rangers recruited Bulkeley in Littleton Mass for 1757. Bulkeley knew local men (including brother Peter) from Peirce’s company, who may in turn have directed Roger’s recruiters to their comrades living deeper in Middlesex county.

In January 1758, Robert Rogers received orders to raise five new companies of rangers. Rogers wrote:

I immediately sent officers into the New England provinces where, by the assistance of my friends, the requested augmentation of Rangers was quickly completed, the whole five companies being ready for service by the 4th day of March. Four of these companies were sent to Louisburg to join General Amherst, and one joined the corps under my command.

The one company that joined Rogers at Crown Point included Ensign Robert’s 20-year-old cousin, Edmund Munro, who served as Rogers’ adjutant that year. I find no evidence Robert was in this company. I’ve seen assertions that Robert is named in Edmund Munro’s orderly book, but I found only an unrelated “Doctor Munro” in the copy the Lexington Historical Society provided me, so I believe this claim to be in error.

Massachusetts raised many men for the 1758 campaign in New York, but if Robert served with a provincial company his name would arguably appear in the billeting records. Since no one tried to get Massachusetts to paid for feeding him on his way to New York or back, he probably (but not definitively) never made that trip as a Massachusetts officer or private soldier.

By elimination, if Robert didn’t serve with Massachusetts, and wasn’t in the same company of rangers in New York as his cousin Edmund, the remaining option (if Robert served at all) is that Robert went to Louisburg. And only rangers went to Louisburg.

One more point suggests Hudson had access to sources we no longer enjoy: He says “Ensign Robert Munroe” served in 1758, but “Robert Munroe” in 1762. Since he was specific about the use of the title, he seems to have only used it where he had documentation. So, Hudson must have had reason to believe Robert served as an officer that year, probably the same source that told him Robert went to Louisburg.

All of which leads to the following plausible French War service for Robert Munro:

- 1755: Documented Ensign of Peirce’s Co. Battle of Lake George.

- 1756: Possible 2nd year with Peirce but not deployed.

- 1757: Peirce’s co. probably not raised. Munro stays home.

- 1758: Munro probably joined Rogers Rangers as an officer in January, before Massachusetts raised any men. Sent to Louisburg.

- 1759: Possible 2nd year with Rogers Rangers.

- 1760: Possible 3rd year with Rogers Rangers.

- 1761: Rogers Rangers disbanded.

- 1762: Documented private soldier in Whiting’s Company.

I confess so some mild skepticism about the last year. After years of service as an officer, why would Robert, at age 50, serve as a private in 1762? It seems possible Robert’s 17-year-old son Ebenezer, a minor, used his father’s name to join his cousins Stephen and Josiah without permission.

Or perhaps Robert had simply grown weary of leadership.

Sources

Blodgett, Samuel, Prospective Plan of the Battle Near Lake George, November 1755: Description and illustration.

Effingham de Forest, Louis, The Journals and Papers of Seth Pomeroy, Sometime General in the Colonial Service, 1926: Battle description, number of men killed, etc.

Hough, Franklin B., Journals of Major Robert Rogers, 1883.

Hudson, Charles, History of the Town of Lexington and Genealogical Record, 1868.

Hudson, Charles, History of the Town of Lexington, Revised and Continued by the Lexington Historical Society, 1912.

Jacobus, Donald, Bulkeley Genealogy, 1933

Johnson, Sir William, Report to Governors, Sep 9, 1755

Munro, Edmund, Rogers Rangers Orderly Book, 1758, Lexington Historical Society

Rogers, Mary Cochrane, A Battle Fought on Snow Shoes, 1917.

Sewall, Samuel, History of Woburn, 1868.

Winslow, General John, 1755 Journal, Nova Scotia Historical Society.