American narratives of the Lexington fight have always placed Major Pitcairn at the front of the British troops, wielding his sword as he commanded them to fire on Parker’s militia. Over the past century, such accounts have come into question to the point that the historical moment may, someday soon, disappear from the record entirely.

But what if the only problem is that the Americans named the wrong officer? New research suggests the man mistakenly called “Major Pitcairn” may have instead been the other British field officer known to be present.

His name was Major Edward Mitchell.

Two British Commanders in the Lexington Fight

American eyewitnesses consistently, and from the very beginning, noted the presence of multiple British “commanders” on Lexington Common when the first shots were fired, even if no deposition or narrative overly focused on the point.

Within days of what locals referred to afterward simply as “the fight”, spectator Thomas Price Willard—the new town schoolmaster—signed a deposition that included this statement: “the commanding officers said something, what I know not; but upon that the [British] Regulars ran. . .”[1] His statement documented a moment uncorroborated at that time by other eyewitnesses. Willard’s testimony goes notably uncontested, however, as others don’t touch on what happened before the British advance, nor bother to differentiate between commanders and the some two dozen subordinate British officers present.[2]

Many eyewitnesses didn’t even presume to distinguish between officers and private soldiers. Benjamin Tidd and Joseph Abbott said, “some of the regulars who were mounted on horses”. Levi Harrington and Levi Mead said the same, adding, “which we took to be officers.” Similarly, Elijah Sanderson said, “I heard one of the regulars, who I took to be an officer, say ‘Damn them, we will have them.’”[3]

Other than Willard, only three witnesses—militiaman John Robbins and spectators Thomas Fessenden and William Draper—reported seeing “officers” without any qualification. Of these, only Draper mentions a commander, stating, “the commanding officer of the troops (as I took him) gave the command to the troops ‘Fire! Fire! Damn you, fire!’ and immediately they fired.”[4]

Whether Draper’s “commanding officer” was one of the “commanding officers” reported by Willard is impossible to conclude from the 1775 depositions alone. Yet the existence of more than one officer acting like a commander, at least in the eyes of Willard, stands undisputed. As for the identity of the officers, the American depositions—all signed the week of 24 April 1775—notably include no names.

Willard’s commanders clearly hadn’t introduced themselves.

Published British Accounts Provide Names

In early May, 1775, a loyalist printer published General Thomas Gage’s “Circumstantial Account” of the Lexington fight. The general’s statement names the two senior officers in charge of the Concord expedition: “Lieutenant Colonel Smith of the 10th Regiment” and “Major Pitcairn” of the Marines. The account stated Pitcairn was present on the common but remained mute on Smith’s whereabouts.[5] Separately, however, the patriot newspaper Essex Gazette published several intercepted letters from British soldiers, one of which said, “Col. Smyth of the 10th Regiment ordered us to rush on them with our bayonets fixed.”[6]

Piecing these sources together (likely with others), Lexington eyewitnesses matched—incorrectly, it turned out[7]—the names of two senior British officers in the newspapers to the two “commanders” they saw on their village green.

Several subsequent accounts of the Lexington fight specifically name both “Smith” and “Pitcairn”:

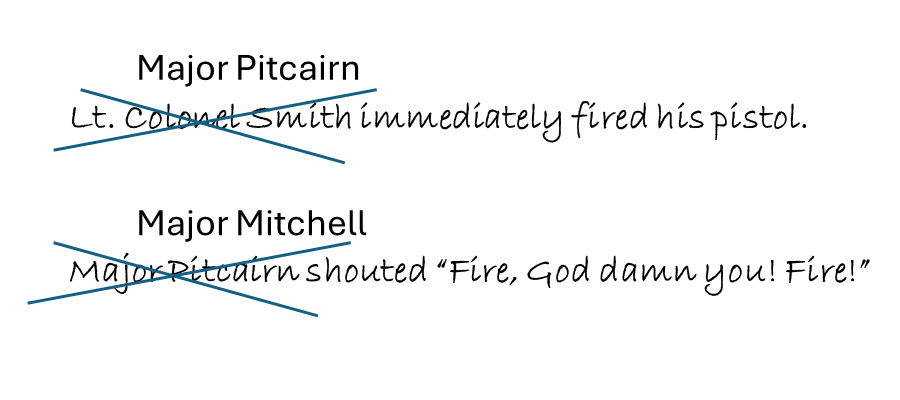

In 1776, Reverend Jonas Clark’s stated “three officers (supposed to be Col. Smith, Major Pitcairn, and another officer)” shouted orders to disarm and disperse and “the second of these officers. . . fired his pistol towards the militia as they were dispersing.”[8]

In 1825, William Munro, one of the surviving militiamen, stated: “Maj. Pitcairn advanced and, after a moment’s conversation with Col. Smith, he advanced with his troops and . . . he [Pitcairn] said to his men “Fire, damn you, fire!”.[9]

In 1846, spectator Levi Harrington’s also named both Smith and Pitcairn. Harrington, like Munro, names Pitcairn as the officer who rode forward ahead of the troops.[10]

Clearly, schoolmaster Willard was not the only man in Lexington who thought he saw two commanders. Also, the fact that Clark, Munro, and Harrington all assign the same names to the two commanding officers suggests broad agreement in Lexington about who was ultimately in charge. The commander they believed to be most senior, whom they called “Lt. Colonel Smith”, stayed back while the subordinate of the two, “Major Pitcairn”, advanced with the troops and ordered them to fire.

William Munro’s 1825 statement also serves to link the two events reported independently in 1775 by Thomas Price Willard and William Draper. One of the “commanding officers” Willard saw was the same “commanding officer” Draper reported at the head of the troops giving the order fire.

Notably, these eyewitness statements are separated by decades, an indication the “two commander narrative” persisted in Lexington long into the 1800s. As late as 1886, a letter from A.B. Muzzey names the Lexington citizens who played Smith and Pitcairn in the town’s 1822 reenactment, without any indication the presence of both commanders in the “sham fight” was out of the ordinary either when it happened or at the time of Muzzey’s writing.[11]

The Eroding “Two Commander” Narrative

While all of Lexington accepted the presence of two British commanders at the time of the fight, doubts remained as to their identity. William Tidd’s 1824 affidavit says that, once the fight began, he fired his musket at an officer “presumed to be Major Pitcairn”. Tidd knew he shot at the officer who issued the order to fire moments before, yet fifty years later, remained uncertain about the man’s name.[12]

The ambiguity resulted in variations across published narratives of the time. Elias Phinney’s 1825 mentions only “commander Lt. Col. Smith”[13], while an account published in the Boston News Letter the following year names only Pitcairn.[14] Everett’s 1835 address refers only to “the commanders of the British forces.”[15] In 1851, Frothingham wrote Major Pitcairn was “among the officers” giving orders, but names no others.[16]

Lt. Colonel Smith thus fades from the story, and with good reason. None of the British sources placed him on the common at the time of the fight, and his own 1775 report to Gage, which finally found its way into MHS Proceedings records in 1876, confirmed he wasn’t there when the shooting started.[17]

Unfortunately, as Smith departed the narrative, so did the existence of a second “commander”. Varney (1895) still placed Major Pitcairn at the head of the troops, brandishing his sword and giving an order to fire, as does Ellen Chase in 1910 and Frank Coburn in 1912. But none mention a second commander who gave the initial order to disperse, or with whom “Pitcairn” conversed shortly before the final advance.[18]

Once historians determined Major Pitcairn was unequivocally in charge, perhaps they concluded eyewitnesses reporting a second commander—still in the minority—misinterpreted or misremembered what they saw. Or perhaps, since all still agreed on the kernel of the story—the King’s troops fired on orders from Major Pitcairn—no one thought the second commander required identification.

Then came the apologists.

Beginning in the late 1800s, additional British eyewitness accounts came to light containing fresh perspectives of the revolution’s opening skirmish. If taken together with American accounts, they had the potential to greatly clarify the events of 19 April. Unfortunately, so far, they have done the opposite.

These new sources corroborated the first British reports, none of which place Pitcairn at the front of the troops as the Americans claimed. Ensign Henry DeBerniere said Pitcairn “ordered our light infantry to advance and disarm them, which they were doing. . .”, suggesting Pitcairn himself did not advance.[19] DeBerniere’s statement, in the hands of American historians since the late 1700s, agrees with an account from Lieutenant William Sutherland first published in 1927 that reads, “the Gentlemen [officers] who were on horseback rode amongst them [the militia], at which time I heard Major Pitcairn’s voice call out ‘Soldiers don’t fire’. . .”[20], implying the major was somewhere behind the officers at the front, not with them.

Historians have seen little reason to reconcile these conflicting British statements with their American counterparts. If patriotic spirit dismissed inconvenient British sources for the first 150 years, since World War I the situation has reversed; over the past century most scholars have shown little regard for the Lexington eyewitnesses. Harold Murdock thought the 1820s affidavits published by Phinney and Ripley, however rich in detail, were best “reserved for appendices and illustrative notes, and not included in the body of any historical work”. Arthur Tourtellot called them “the long-winded recollections of old men”.[21]

As a result of these biases, the documented second British commander—his actions, his identity, even his existence—has gone completely uninvestigated. Tourtellot’s 1959 Lexington and Concord has Pitcairn firmly in command, not from the front but from the west side of the green.

The gaping hole in Tourtellot’s narrative is wider than all his predecessors. Where none of the American accounts described the events that precipitated the order to fire, with Tourtellot the order never comes. The action jumps directly from the British troops lined up by the meetinghouse on the east side by Buckman Tavern to the melee after the first shots. What happened in between? Tourtellot provides only guesses (yet somehow still felt confident the fight was beyond Pitcairn’s ability to control).[22]

Later narratives have followed suit. Hackett-Fischer’s 1993 retelling places Pitcairn on the field where Tourtellot does, then fades from definitive action into a jumbled list of eyewitness statements and nebulous conjecture. Pitcairn possibly rode forward. Or perhaps that was someone else entirely. If someone shouted “Fire!”, the King’s troops didn’t obey. The narrative explodes into white noise and the static of endless possibilities until, after the first shots erupt, the British regulars charge ahead “without orders”.[23]

Open Questions

Despite these reduced and sometimes revisionist narratives, discrepancies remain.

One key example: The placement of Major Pitcairn by Tourtellot and Hackett Fischer on the west of the meetinghouse originated with a 1775 statement attributed to spectator Levi Harrington by Reverend Gordon, that the field commander “rode round the meetinghouse and came towards the company that way.[24]

No British source corroborates any such movement to Major Pitcairn. Pitcairn’s own report to Gage states that, after the fight began, “several shots were fired from a meeting house on our left,”[25] presumably a reference to Pitcairn’s own position on Bedford Road near Buckman Tavern during the fight.[26]

This location not only agrees with every British source, but also with the original American statements that the senior commander they called “Smith” did not advance with the troops. And all British sources agreed Pitcairn was the senior commander. The obvious conclusion, therefore, is that from the beginning, Lexington witnesses assigned the wrong names to the commanders they saw. Pitcairn was the officer they called “Lt. Colonel Smith” and their “Pitcairn” was somebody else.[27]

Correcting this mistake snaps both sides into sudden agreement. None of the Americans say a senior commander ordered the British troops to fire on Parker’s militia from the rear.[28] Nor do any British sources. Since there is no evidence to the contrary, at this late date we can only conclude that, as the British have said since the beginning, Pitcairn never ordered the King’s troops to fire.

But by the same logic, a British officer at the front of the troop did give the order. Dozens of Americans said so, and no British account denies it.

So, who was the officer the citizens of Lexington called “Major Pitcairn”, who rode around the meetinghouse, had a word with the real Pitcairn, then advanced with the troops? Who fired his pistol and ordered the troops to “Fire! God damn you, fire!”? Who, after the first volley of musket fire, chased Lieutenant Tidd up Bedford Road, saber in hand?

A likely answer exists. Lieutenant William Sutherland’s 1775 report includes a list of British “gentlemen” on horseback at the head of the troops on Lexington Common. Most are “company grade” officers, captains and lieutenants unlikely to have acted like a “commanding officer”. One, however, was newly promoted Major Edward Mitchell, the only other British field officer known to be present that morning, who rode right where the Americans said a “commanding officer” ordered the troops to open fire.

Who Was Major Edward Mitchell?

Edward Mitchell[29] is first found in British army records as a captain in the short-lived 120th Regiment of Foot, which organized in 1762 only to be disbanded the following year. After several years on Irish half-pay, in 1766 Mitchell traded into a captaincy in the 17th Dragoons, a regiment of light cavalry (alternatively “mounted infantry”) trained to fight with both swords and muskets whether on foot or horseback.[30]

After eight years as a dragoon captain, in January 1774 Mitchell obtained a major’s commission in Lord Percy’s 5th Regiment of Foot.[31] Shortly after, Major Mitchell and the 5th moved from Ireland to Boston to help enforce Parliament’s “Massachusetts Government Act”. When they landed in early July, 1775,[32] Mitchell was one of the most junior field officers in the Boston garrison.[33]

Mitchell must have served well, since in 1777 he promoted to Lieutenant Colonel of the 27th Foot.[34] Like Major Pitcairn and so many others, however, he did not survive the war.[35] Neither did any report he might have provided Lord Percy and General Gage about his actions on 19 April 1775.

Fortunately, others mentioned him by name.

Was Major Mitchell The Second British “Commander” in the Lexington Fight?

The first part of Major Mitchell’s activities are documented by both British[36] and American sources:

On Tuesday 18April, General Gage placed Mitchell in charge of “a small party on horseback” tasked with preventing news of Smith’s expedition from reaching Concord.[37] Mitchell’s background with the dragoons, often assigned reconnaissance and skirmishing work, made him a logical choice for the assignment.

Around ten o’clock that evening, on the road between Lexington and Concord, they made prisoners of three Lexington scouts sent to discover their business. Around two o’clock the next morning they stopped Paul Revere, who told Mitchell he “had alarmed the country all the way up, and that their boats had catched aground, and I should have 500 men there soon”.[38]

Realizing he had failed his assignment and might soon be surrounded, Mitchell decided to retreat. They released their prisoners and galloped through Lexington down the road to Boston.[39] They met up with the detachment of light infantry in the next town, Menotomy.[40]

What happened to Mitchell and his men after they met Pitcairn’s detachment remained a mystery until Sutherland’s report for General Gage came to light in the 1920s. In the margin, written by the same hand as the rest, lies the note, “It is very unlikely that our men should have fired on them [the militia] immediately as they must certainly have hurt Major Mitchell, Capts. Lumm, Cochrane, Lieuts. Baker, Thorne, & me & some other Gentlemen who were on horseback who rode in amongst them, desiring them to throw down their arms and no harm should be done them.”[41] Later in the main body of his report, Sutherland says, “some of the villains were got over the hedge, fired at us, and it was then and not before that the soldiers fired.”

Sutherland does not reveal who ordered the soldiers to fire, or even that anyone did. His report simply skips over the point, just as the American statements tactfully omit the shot fired from the “hedge”.[42] However another British officer, Captain William Soutar of the Marines, says the front light infantry company fired in response to a shout from the “leading company”, presumably a reference to the mounted officers in front. Since Soutar says the front light infantry “immediately formed and fired”, it seems reasonable to conclude they thought the “shout” was an order to fire, just as American witnesses reported the British “commanding officer” issued.

How can we be sure Mitchell was the officer at the front who gave the order to fire? We probably can’t, but several facts support the idea:

First, Major Mitchell held seniority. Excepting Sutherland himself, the other listed officers belonged to Mitchell’s party the night before and were likely still under Mitchell’s command. Assuming they looked to Mitchell for orders, Mitchell would have looked like a “commander” of the group.

Second, as the only field officer at the front, Mitchell alone could command the company grade officers standing on the ground with the private soldiers, none of whom would repeat an order to fire to their men had they come from an officer of equal or lesser rank, especially if, from behind them, they heard Pitcairn shouting the opposite moments earlier.

Third, the “commanding officer” on Lexington Common sounds like Mitchell. The man who “in a passion”[43] ordered the King’s troops to “Fire! God damn you! Fire!”, then chased William Tidd up Bedford Road, sword in hand, shouting “Stop or you are a dead man!” sounds much like the named Major Mitchell, who three hours earlier thrust a pistol against Paul Revere’s head, threatening to “blow his brains out” if he didn’t tell the truth.[44] An officer fond of the phrase “dead men”. In addition to Tidd’s statement above, militiaman Sylvanus Wood said the officer swinging his sword in front of the King’s troops shouted “Lay down your arms, you damned rebels, or you are all dead men!” And both Elijah Sanderson and Paul Revere reported that, upon their respective captures on Concord Road, an officer said they were “dead men” if they resisted.[45]

Finally, we have the field commander’s sword. William Tidd said he was chased up Bedford Road by the man “presumed to be Pitcairn”. Separately, Levi Harrington’s 1846 account said Tidd’s pursuer wielded a “sabre”, a three-foot blade carried by cavalry officers, and dragoons. Infantry officers invariably favored shorter “hangers” that didn’t drag in the dirt as they marched. Pitcairn the marine was equally unlikely to own a saber. On the other hand Major Mitchell, the former dragoon captain, was likely one of few infantry officers in Boston who owned a saber and, since he rode out from Boston, carry one the day of the fight.[46]

Is Mitchell’s senior rank subordinate only to Pitcairn, his status as a field officer, his threatening language, and his unique background as a dragoon captain enough to conclude he was the “Major Pitcairn” who ordered the British to fire on the Americans? The verdict, I suppose, depends on the jury.

At a minimum, Mitchell is a prime suspect.

Sources

Chase, Ellen: Beginnings of the American Revolution, 1910.

Clark, Reverend Jonas: Mr. Clark’s Sermon April 19, 1776, 1776.

Coburn, Frank Warren: The Battle of April 19, 1775, 1912.

Dana, Elizabeth et al.: The British in Boston, 1924.

Everett, Edward: An Address Delivered At Lexington, 1835.

Force, Peter: American Archives 4th Series Volume II, Undated.

French, Allen: General Gage’s Informers, 1932.

Frothingham, Richard: Siege of Boston, 1851.

Gage, General Thomas: A Circumstantial Account, 1775. See the Massachusetts Historical Society Online Collection for a digitized copy of the original broadside. The Library of Congress offers a transcript.

Gordon, Rev. William: Letter to Englishman, 17 May 1775, Reprinted by the Philadelphia Gazette 7 June 1775 (Retrieved from Newspapers.com Feb 2024).

Hackett Fischer, David: Paul Revere’s Ride, 1994.

Harrington, Bowen: An Account of the Battle of Lexington – 19 April 1775 by Levi Harrington, an Eyewitness, 1846. The Lexington Historical Society has copies of an 1859 transcript.

Murdock, Harold: The Nineteenth of April 1775, 1923.

Murdock, Harold: Late News of the Ravages, 1927.

Murdock, Harold: The Concord Fight, 1931.

Phinney, Elias: History of the Battle at Lexington, 1825.

Ripley, Ezra: History of the Fight at Concord, 2nd Edition, 1832.

Tourtellot, Arthur B.: Lexington & Concord, 1959.

Varney, George: The Story of Patriot’s Day, 1895.

[1] Force, p490.

[2] A count suggests at least twenty-five British officers. The detachment consisted of at least six infantry companies with a standard three officers each, equating to eighteen captains, lieutenants, and ensigns. While the 4th light infantry marched without its captain, at least one officer—Lt. William Sutherland—was a volunteer extra. Major Pitcairn had at least one extra officer with him—Ensign DeBerniere, acting as a guide—and possibly more. And finally, a British account places on the common the five officers who had been out all night controlling intelligence.

[3] Force, p489-495.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Gage, p1.

[6] Essex Gazette, May 12 1775

[7] This letter appears to be a reference to a bayonet charge ordered by Smith to clear a hill outside Concord held by American militiamen when they first arrived in at their destination, not the Lexington fight which happened before or the fight at Concord’s North Bridge, which happened afterward. See Kehoe p174.

[8] Clark, Appendix “A Narrative, &c.”, p3.

[9] Phinney, p34.

[10] Harrington, p1.

[11] Lexington Historical Society Online Collection, Accession #8819, 17 June 1886, “Letter from A.B. Muzzey giving account of the Lexington Reenactment, 19 April 1822”: “There was Gen. Chandler who personated Maj. Pitcairn, Maj. B. G. Wellington who represented Col. Smith”

[12] Phinney, p37-8.

[13] Phinney, p20. Phinney’s account may have been based on the 1824 affidavit of John Munroe Jr., which mentions only Smith by name and is written in such a way that the actions of both commanders might be interpreted as coming from the same officer. See Phinney, p35-6.

[14] Boston News Letter and City Record, 3 June 1826, p281. No byline.

[15] Everett, 1835, p20.

[16] Frothingham, 1851, p62.

[17] MHS Proceedings, Series 1, Vol 14, p350.

[18] Varney, p33; Chase, p364-367; Coburn, p63-5; Chase also presented a neutral version of the fight’s opening shots based on then newly available British sources.

[19] MHS Collections, Series 2 Vol 14, 1816, p216, “Narrative of occurrences 1775”.

[20] Murdock, 1927, p17.

[21] Murdock, 1923, p6. Tourtellot, p289: He actually said “garrulous”, which Oxford defines as “excessively talkative, especially on trivial matters”, i.e. long-winded.

[22] Tourtellot, p132-134.

[23] Hackett Fischer, p193-4.

[24] Gordon’s Letter, Philadelphia Gazette, 7 June 1775

[25] French, 1932, p53.

[26] Remaining on the east side of the meetinghouse arguably made the most tactical sense for Pitcairn since the enemy commander, Captain Parker, also reportedly stood on the east side of his militia. If Pitcairn rode around the meetinghouse to the west side, he would have been out of earshot if Parker wanted to, for example, communicate his surrender.

[27] The origin of this error is possibly the soldier’s letter in the May 12 1775 issue of the Essex Gazette, which stated the bayonet charge occurred on Smith’s orders. Since Smith was not present, the anonymous soldier clearly conveyed faulty information, but then he did not expect his personal letter to become public record.

[28] Levi Harrington’s 1846 account says the senior commander, who he called “Smith” ordered the troops to fire over the militia’s heads, not at them.

[29] Little is certain about Mitchell’s origins. He may have belonged to the Mitchells of Castlestrange in County Roscommon, a landowning family of Irish-born Scots with many officers in their lineage, and several Edwards. Yet efforts to establish a solid link have so far proven unfruitful.

[30] British National Archives Online Collection, 29 May 1766 Letter from Earl of Hertford to Mr. Secretary Conway: “Requesting that Captain Chudleigh Morgan of the 17th Daragoons (Lt. Colonel Lord Newbattle) be permitted to exchange with Captain Edward Mitchell of the late 120th Regiment of Foot upon the Irish Establishment of half pay. Dated at Dublin Castle.”

[31] 1774 British Army Regiment Lists, 5th Regiment of Foot.

[32] Numerous sources document the arrival of Percy’s 5th in Boston. See “Rowe’s Diary” in Mass. Hist. Society Proceedings, Series 2, Vol 10, p87.

[33] 1775 British Army Regiment Lists for the eleven regiments in Boston show only Major James Ogilvie of the King’s Own had a commission dated later than Mitchell (Apr 1774 vs Jan 1774).

[34] 1779 British Army Regiment Lists, 27th Regiment of Foot, commission dated “3 Nov 1777”.

[35] Inman, George, Losses of the Military and Naval Forces Engaged in the War of the American Revolution, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 1903, Vol 27, No 2, p192: “27th Regiment, Lt. Col. Mitchell, On board the Beaver Prize which was lost in the Hurricane in the West Indies”. The HMS Beaver’s Prize wrecked on St. Lucia 11 Oct in the “Great Hurricane of 1780”. Seventeen crew survived. Evidently Mitchell did not.

[36] See Murdock, 1927, p27-32, “Richard’s Pope’s Book”.

[37] French, 1932, 31-32.

[38] Revere, Paul, 1775, Deposition, Mass. Hist. Society Online Collection.

[39] Ibid. Also Phinney, p32.

[40] Murdock, 1927, p14.

[41] Murdock, 1927, p17, footnote.

[42] Likely a “Devon hedge”, i.e. a stone wall, as other British accounts state.

[43] Harrington, p1.

[44] Revere’s 1775 deposition.

[45] While its possible some occurrences of this common phrase came from other officers, not all British behaved the same. Contrast Mitchell’s “harsh” words with Revere’s statement that another British officer that night (possibly Captain Lumm, the ranking officer under Mitchell) was “much of a gentleman”, or with Stiles description of Pitcairn as “a good man in a bad cause”. No such statements about Mitchell exist.

[46] While Levi Harrington’s 1846 account may be imprecise with its details, Levi the eyewitness likely knew the difference between sabers and hangers from his father’s blacksmith shop as well as his later army service. Levi also had occasion to see the blade firsthand, since several American eyewitnesses said the commander brandished it before his order to fire.