Early Life

William Tidd was born in northern Lexington in 1736, the seventh of ten children to Daniel and Hepzibah (Reed) Tidd. William’s parents descended from two original proprietors of Cambridge Farms (as Lexington was first called), John Tidd and William Reed. William took his name from his mother’s side; his grandfather William “Captain” Reed had been the town’s largest landowner, and his uncle William “Squire” Reed was a prominent town leader for the first half of William (Tidd)’s long life.[1]

William Tidd’s father Daniel served as town selectman and assessor almost as long as his brother-in-law. Daniel bore the title “Ensign”, which first appeared in 1746 town records during King George’s War, the third of four conflicts between Britain and France. Daniel is conspicuously absent from town meetings from 1743-46, so he probably served as a militia officer during those years. Daniel’s years of civil and military service set a precedent his son would later repeat.[2]

William Tidd lived his entire life on a farm off Bedford Road (now Hancock Street), two doors up from the Hancock-Clarke parsonage, about a mile north of Lexington Common. The land had once belonged to his grandmother Lydia Tidd. Daniel Tidd appears to have built the “old Tidd House” around 1730, a dignified two-story colonial that still stands today (in 2024). Affluent if not wealthy during his lifetime, William owned 75 acres of fields and woodlots at the time of his death, plus half a pew in the meetinghouse.[3]

The Seven Years War

Like many in their early twenties during the last war with France (aka the Seven Years War (1755-1762) or the French and Indian War, depending on which nation’s history book is referenced), William served in the town militia. Most records have been lost, but the name “William Tidd” appears on a 1759 list of men in Lexington’s “military company of foot” who received bayonets. Other men listed on the same roll: John Parker, Francis Brown, Jonathan Harrington, and a half-dozen more who would stand with William on Lexington Common sixteen years later.[4]

The French War took a heavy toll on the Tidd family. After the failed English campaign at Lake George in 1758, William’s 18-year-old cousin Samuel succumbed to one of the deadly diseases sweeping the camp. William’s older brother Daniel, 32, whose name appears on provincial regiment rolls, likewise did not survive the war (circumstances unknown).[5]

War with France ended for good in 1762 with British victory in North America. In 1766, William married Ruth Monroe, daughter of Ensign Robert Munro. Their marriage lasted sixty years.

Unusual for the era, they had only one daughter (also Ruth) in 1767, which suggests complications that prevented future children. I imagine William and Ruth closely examined the newborn girl’s hands and feet. William’s grandmother Reed had been born with extra fingers and toes, and it was said the condition would reappear every few generations.[6]

In the pre-revolution years, William spent most of his time farming. He and brother-in-law Daniel Harrington rented the town’s “best meadow” in 1768. He occasionally worked on Reverend Clark’s farm with his oxen. He held minor town officers: deer reeve and fence viewer, surveyor of highways and tythingman. His name appears frequently in town records related to providing clothing, food, and housing for the town poor.[7]

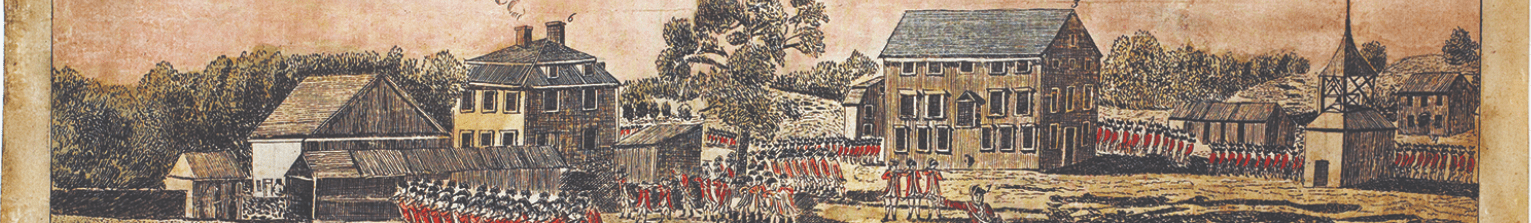

The Revolution

William (with several other Lexington men) had known revolutionary leader John Hancock since they were boys. After his father’s death, Hancock lived with his grandfather at the town parsonage, two doors from the Tidd farm. For some period (sources differ, but likely several years), William and John attended grammar school and Sunday services together.[8]

Thirty years later, fate would have Hancock hiding out in Lexington surrounded by his “kinsmen and friends”.[9]

In February 1775, William’s militia experience and standing in the community proved sufficient for his selection as Captain Parker’s sole lieutenant in the volunteer Lexington Militia Company. Others in town had more military experience, but had also taken loyalty oaths that, before the outbreak of hostilities, may have created unacceptable legal risk. As Edmund Munroe, a French War lieutenant from Lexington, reportedly said, “I’m with you boys. I won’t help you get into trouble. But if you do get into trouble I’ll help you get out.”[10]

Several anecdotes attest to William’s leadership. On the night of April 18, the militia drilled at his house. When Paul Revere brought news of the approaching regulars, William directed the spread of the alarm around Lexington. And as Pitcairn’s detachment approached the Common, William stood next to Captain Parker at the front of the line.[11]

Standing behind Parker and Tidd were William’s younger brother Samuel, several Reed and Tidd cousins, in-laws Samuel Hastings and Amos Marrett and the many Munros, plus other extended relatives and neighbors. As much a family meeting as any of Reverend Clarke’s Sunday services.[12]

The shooting reportedly lasted fifteen minutes.[13]

After the fight, William signed a carefully worded joint deposition stating he was one of Parker’s men already dispersing when the regulars began shooting, shots that occurred before any gun was fired “by any person in our company”.[14]

In an 1825 individual affidavit, William added:

I then retreated up the north road, and was pursued about thirty rods by an officer on horseback (supposed to be Maj. Pitcairn.) calling out to me, “Damn you, stop, or you are a dead man!”

I found I could not escape him unless I left the road. Therefore I sprang over a pair of bars, made a stand, and discharged my gun at him; upon which he immediately turned to the main body.[15]

William’s activities later in the day on April 19th are unknown, though he continued his one-year term as lieutenant of Parker’s Company during the Siege of Boston. He is named with those from Lexington who served in the 1776 campaign to White Plains. For the remainder of the war William served on town committees charged with raising men to serve in the continental army. [16]

During this time William lost his parents, both then in their early eighties.[17]

In September 1777, William paid (with others) to send an additional soldier to Bennington during the Saratoga campaign. That soldier was probably Adam Tidd, a slave purchased in 1752 by William’s father. After serving three years (at least), Adam settled in Boston a free man, married and raised a family. Adam’s son, Porter Tidd, became a popular musician and early civil-rights activist.[18]

Later Years

For the next twenty-five years, William served frequently as town selectman and/or assessor alongside several other veterans of Parker’s Company. According to 1787 town meeting records, he organized the town’s response to Shay’s Rebellion. In 1795, he oversaw the fundraising for the construction of new schoolhouses.

His only daughter married Nathan Chandler in 1785. William and Ruth soon had three grandchildren: a girl and two boys, who grew to marry into the Mulliken and Harrington and Mead families.

William finally retired from public service in 1799, succeeded by his son-in-law. The Honorable Nathan Chandler went on to serve as town selectman, representative, and state senator for the next three decades. Chandler’s eldest son followed in his father’s public service footsteps. Both sons served in the town rifle company.[19]

According to Reverend Clark’s journal, William transacted some minor farm business with the parson. Working with his oxen, selling food, etc. Wiliam also paid the minister interest on a bond held by Clark’s sister-in-law, Elizabeth Bowes, who fled Boston during the siege. Perhaps to fund her relocation Ms. Bowes sold some possessions to the Tidds, who paid in installments.

Anecdotes suggest he was known as “Master Tidd” around town. Daniel Harrington’s children (and likely many others in William’s extended family) called him “Uncle Bill”.

Years later, he was remembered by A.B. Muzzey as short of stature, with a compact frame and an erect gait, active even in old age. Children passing his farm on their way to school often found working outside.

William wore a red wool cap of a revolution veteran—possibly of the Phyrgian liberty style—to Sunday meeting. He “belonged to the old school, who kept their seats in their pews after the service and bowed to the minister as he passed out first.”[20]

William lived to see several great-grandchildren (Ruth, their great-great-grandchildren). William died in 1826, his 91st year, retaining his faculties “to a great degree” until the end. Ruth, “a fitting partner”, lived thirteen more years, to age 97.[21]

The Handshake

One moment speaks to William Tidd’s reputation more than perhaps any other on record.[22] In November 1789, a year after William stepped down as selectman, George Washington visited Lexington on his first tour of the country as its new president. Standing on the Common with the town’s new leadership and many veterans of “the fight”, Washington asked for one man by name:

“Where is Leftenant Tidd, who was next to Captain Parker?”

They brought William forward. Washington offered William “a fine grasp of the hand”. The two old soldiers, one who happened to be the first President of the United States, shared a moment in the place where, fifteen years before, a fifteen-minute firefight precipitated the existence of a great nation.

According to witnesses, neither man saw the need to speak.

Sources

Barry, John Stetson, The History of Massachusetts, The Provincial Period (Volume 2), 1857.

Calabrese, Carmin F.: Lieutenant William Tidd, Retrieved from LexingtonMinutemen.com 2024

Canavan, M.J., Canavan Papers, Three Volumes, 1912

Force, Peter, American Archives 4th Series Volume II, Undated

Gordon, Rev. William: Letter to Englishman, 17 May 1775, Reprinted by the Philadelphia Gazette 7 June 1775 (Retrieved from Newspapers.com Feb 2024)

Gosse, Van: The First Reconstruction: Black Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War, 2021

Hudson, Charles: History of the Town of Lexington & Genealogical Register (G. R.), 1868

Hudson, Charles: History of the Town of Lexington, Revised and Continued by the Lexington Historical Society, 1912

LHS I: Lexington Historical Society Proceedings Vol I, 1889

MMR-93: Massachusetts Muster Rolls 1749-1755, Volume 93, Microfilms on FamilySearch.org, Retrieved Jan 2024

MRR-15: Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, Volume 15, 1907

Phinney, Elias: History of the Battle at Lexington, 1825

Sewall, Samuel, History of Woburn, 1868

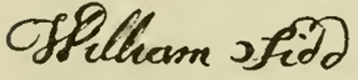

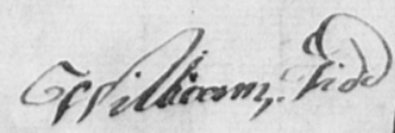

Signatures

Two signatures believed to be from William Tidd’s hand survive. The first comes from Lexington’s 1780 Assessor’s Book.

The second (shown at the top of this post) comes from a 1776 oath of allegiance to the “United American Colonies”.

[1] Hudson 1868, G.R., p240-4; Hudson 1868, G.R., p191-2; Woburn and Lexington vital records, plus Ancestry.com searches, show no earlier Tidd of the name William.

[2] Hudson 1868, p403-5; Hudson 1912, Vol II, p698

[3] Hudson 1868, G.R., p38,41; Canavan, Vol 1, p14; Calabrese, p1

[4] Hudson 1912, Vol I, p417; Barry, Vol II, p235-6; Lexington Historical Society, Pew Deeds

[5] Barry, Vol II, p194-96; Sewell, p555-556; MMR-93, image #449; Hudson 1868, p243

[6] Hudson 1868, G.R., p191: Grandmother Abigail Kendall Reed polydactyly.

[7] Lexington Town Records, 1755-1778.

[8] Hudson 1912, Vol II: Men living in 1775 Lexington born within a year of John Hancock (therefore likely grammar school classmates, etc.): John Bridge, Francis Brown, David Fisk, Henry Harrington, Joseph Mason, Benjamin Merriam, Edmund Munro, Joshua Simonds, and William Tidd.

[9] A. B. Muzzey, “History of the Battle of Lexington”, Oct 1877, NEHGR.

[10] Canavan, Vol II, p268;

[11] Phinney, p37; Phinney, p36: Ebenezer Munroe stated, “Lieut. Tidd requested myself and others to meet on the common”; LHS-I, p xxxix

[12] Hudson 1868, p384; Hudson 1912, Vol II, p698

[13] See Gordon for Paul Revere’s estimate.

[14] Force p492

[15] Phinney p37-38

[16] Hudson 1868, pp385, 388, 391-2; “William Tidd” is also listed with three years on the Continental Line, however the conflict with his town service raises the question of whether a younger cousin (born in New Braintree with the same name) filled the Lexington quota.

[17] Hudson 1868, G.R., p243;

[18] Hudson p389; LHS Archives [71 MSS in Ledgers: Book W. p. 55, Bill of Sale for a Slave Boy]; MRR-15, p469 “Teed, Adam”, p 730 “Tidd, Adam”; Ancestry.com records; “Eastern Argus Tri Weekly,” 1833-12-09, pg. 2 [Retrieved from Newspapers.com Mar 2024]; Gosse p197-200

[19] Hudson 1868 p403-5; Hudson 1868, G.R., 40-41;

[20] G.W. Sampson, LHS-I, “Robert Munroe”, p39, p xxxix;

[21] 1820 Census Records, Lexington, “Nathan Chandler”; Ancestry.com records; Hudson 1868 p244

[22] Sally Munroe, LHS-I, “Washington’s Visit to Lexington”, p xxxix